EXECUTIVE POWER, ESSENTIAL PRAYER: The War Over Worship During a Pandemic

A year after Agudah won landmark court rulings overturning New York’s Cluster Action Initiative, plaintiffs recount the story of a legal battle that shaped religious liberties in a pandemic and beyond.

***

It was late afternoon of Hoshanah Rabbah 2020 when Shlomo Werdiger’s cellphone rang. On the line was a very unhappy New York governor. And an angry Andrew Cuomo was not a man to be messed with — particularly for an organizational leader who regularly lobbied the state government.

“The governor told me that if we back him into a corner and take him on, it’s not going to bode well for us,” recalls Mr. Werdiger, Chairman of Agudath Israel of America’s Board of Trustees.

Mr. Werdiger’s transgression was releasing a video statement vowing that Agudah would continue its legal battle against Mr. Cuomo’s Cluster Action Initiative, which had essentially shut shuls.

The governor, who had a high approval rating and was firmly ensconced in the Executive Mansion in his third term and likely going on to a fourth, was not known to suffer lightly those who stood up to his authority.

Was it worthwhile for Agudah to push on with a lawsuit that might or might not succeed on its merits, but would surely alienate the powerful man atop New York State government for the foreseeable future?

***

Amid a rise in COVID-19 test-positivity rates in some portions of New York State in the fall of 2020, officials warned that severe restrictions, which had eased in phases throughout the preceding summer, would be reimposed.

On the morning of Tuesday, October 6, the second day of Chol HaMoed Sukkos, Gov. Cuomo held a conference call with Orthodox Jewish leaders, whose communities were in some of the high-positivity areas. It was the latest of several calls the governor had had with Jewish leaders in recent days, as he argued that houses of worship and schools were prime sources of the coronavirus’ spread.

“We found out yet again that Andrew was chosen to be the liaison with the Orthodox Jewish community back in the administrations of his father, Gov. Mario Cuomo, and what a close relationship he has with the community,” says Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, Agudath Israel’s Executive Vice President, a participant on the calls. After declaring his love for the community, the governor told the Jewish leaders that later that day he would be announcing new shutdowns of businesses and schools — and insisted on strict compliance with the 50% limitation on attendance at houses of worship.

“The current rule … in any indoor gathering … it’s 50% of capacity,” the governor said. “If we don’t follow that law, then the infection rate gets worse. Then we’re going to have to go back to closedown. And nobody wants to do that. But I need your help in getting the rate down, and the rate will come down if we follow the rules on the mask and the social distancing and the 50%.”

The implication was clear: keep the current guideline of 50% capacity, and further restrictions wouldn’t be imposed on houses of worship.

Shortly thereafter, the governor held his press conference and made his announcements. And the Jewish leaders couldn’t believe this was the same person who had spoken on their conference call just hours earlier.

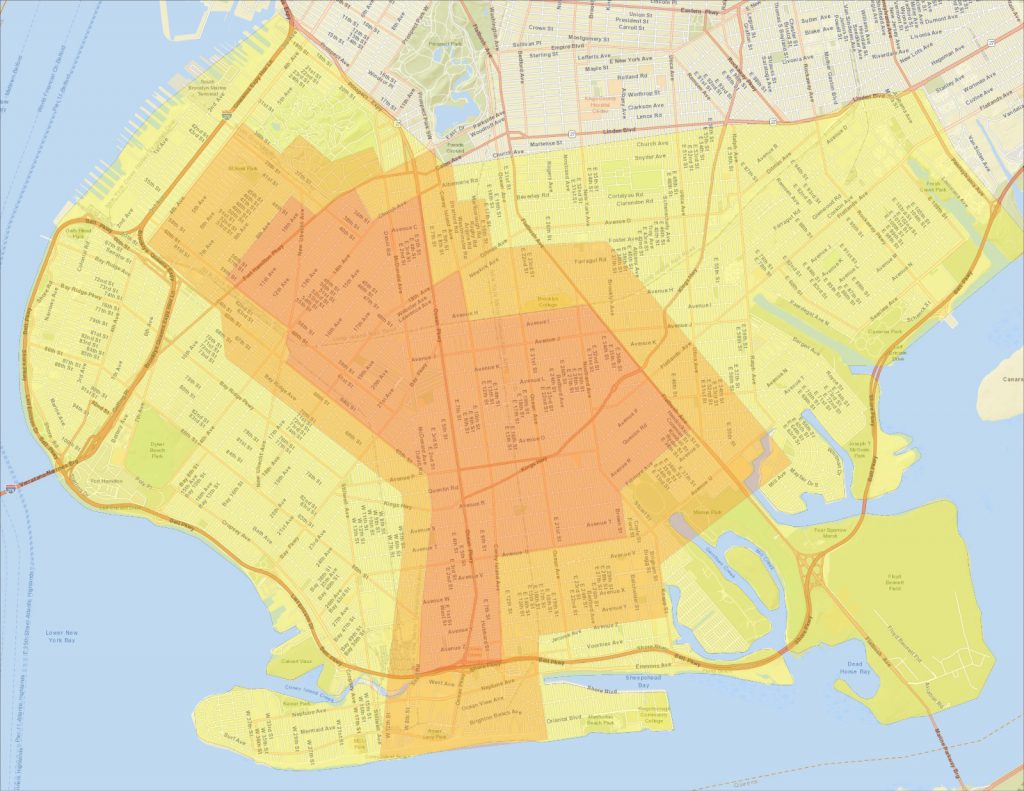

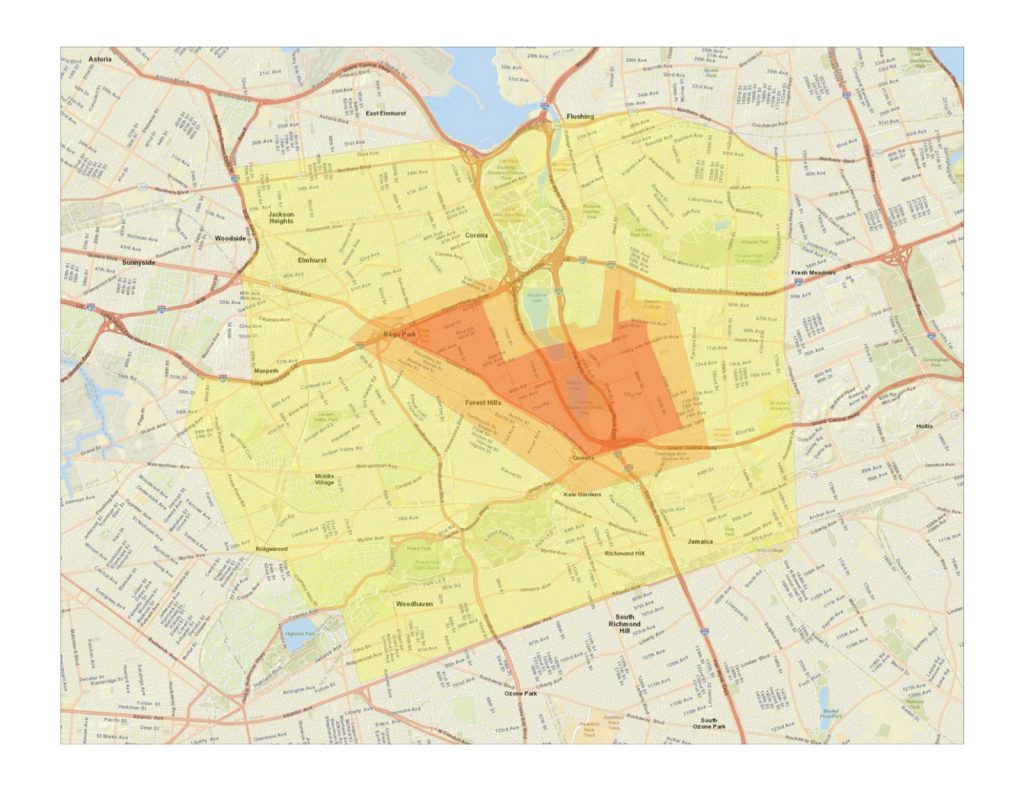

At the press conference, Mr. Cuomo announced a new “Cluster Action Initiative,” categorizing parts of the state into various colored “zones,” based on COVID-test-positivity rates. In the most-restrictive “red” zones, guidelines included limiting services at houses of worship to 10 people — regardless of how big the house of worship was. In the intermediate “orange” zone, attendance at houses of worship was capped at 25 people. In the least-restrictive “yellow” zones, the limit was 50% of occupancy.

Many of the largest Jewish communities in the state, including in Brooklyn, Queens, and Rockland County, found themselves in red or orange zones.

While houses of worship were subject to these limitations, “essential businesses” were allowed to remain open without occupancy restriction in red zones; in orange zones, all businesses were allowed open except specific high-risk ones like barber shops and salons.

“This was something which was quite dismaying and appalling,” says Rabbi Zwiebel. “It was a stunner and a shocker and a display of contempt, frankly, for the people he had just gotten off the phone with.”

Mr. Werdiger, who had also participated in the earlier calls with the governor, says Mr. Cuomo “purposely misled us. He told us something to get us off his back, getting us to think that we have some sort of path forward here with that 50%, then he made an announcement that completely blindsided us.”

In addition to feeling betrayed by the governor, the Jewish community was devastated at the prospect of spending the upcoming Shemini Atzeres and Simchas Torah holidays at home, or in small backyard minyanim, rather than in shul.

Agudah leaders still attempted to engage in diplomacy. On the morning of Wednesday, October 7, Mr. Werdiger spoke again with Mr. Cuomo. When he asked why the governor had backtracked on his earlier comments of keeping shuls at 50% capacity, “the governor gave no plausible excuse,” Mr. Werdiger recalls. “He just kept saying, ‘It’s the science.’”

“I said, ‘Governor, our big holiday is coming up. Imagine if you called up the Cardinal the day before a big holiday, and you told him you can only have 10 people in St. Patrick’s Cathedral? What are you doing here? This is our big holiday.’

“We tried reasoning with him, but it just didn’t go. There was no rational reason for him to do what he did, and he kept hiding behind ‘the science,’ that we know now is really fake science.

“And the health commissioner [Dr. Howard Zucker] wasn’t a big help, either, in terms of quantifying the science and the statistics that they gave us, which we see now was all really contrived and made up and had no basis.”

***

While Mr. Cuomo’s Oct. 6 press conference was still ongoing, Avi Schick, a partner at the Troutman Pepper law firm who has represented Agudath Israel and other plaintiffs in religious-liberties cases, was on an email chain with community leaders discussing filing a lawsuit. And they had to act quickly.

The suit would be predicated on two bases: One was that granting more rights to “essential” businesses than to worshipers was an unconstitutional restriction of religious freedom. However, that would be a tough sell for a district-court judge, after two Supreme Court cases earlier in the pandemic, called South Bay and Calvary Chapel, had ruled against religious-liberties challenges to lockdown restrictions.

But a second argument appeared more promising: that the governor had specifically targeted the Orthodox Jewish community. The governor, at press briefings and media conference calls, was regularly calling out the Orthodox Jewish community as being a source of the virus’ spread. And Agudah had compiled statistics of COVID-positivity rates showing that Orthodox areas of the state were placed into more restrictive zones than non-Orthodox areas with higher or comparable rates.

To obtain a temporary restraining order against the Cluster Action Initiative in time for Shemini Atzeres, a hearing would have to be held no later than Hoshana Rabbah, Friday Oct. 9. This meant fewer than 72 hours for Mr. Schick and his legal team to draft and file the briefs, read the state’s response, file its own response and participate in a virtual hearing before a federal judge of the Eastern District of New York.

***

There was no shortage of plaintiffs lining up to be in the case, including various organizations and the Rabbanim of several Agudah shuls.

Among those most strongly encouraging Mr. Schick to file the suit was his own rav, Harav Yisroel Reisman of Agudah of Madison, who is also Rosh Yeshivah of Torah Vodaath. And Rav Reisman’s motivation was beyond the issue of tefillah b’tzibbur and keeping shuls open for Yom Tov.

“We felt that this had the potential to be a turning point,” says Rav Reisman. “Historically, the Orthodox Jewish community had not seen its religious rights threatened in this country. But over the last decade, things have begun to change. The substantially equivalent education controversy, in particular, was and continues to be a serious threat to the welfare of our yeshivos. During COVID, religious rights and our community in New York had been the subject of a lot of scrutiny. I saw the governor’s outrageous color-coded zones as a particularly unfair attack on our religious liberties. We felt that if we did not try to make statement for our religious rights, we would suffer in the long run. It was not just the minyanim — it was the big picture.

“We felt, correctly so, that if the Supreme Court would side with us, the decision would have religious-liberty aspects that would serve as a precedent that would be useful for future cases. And indeed, one aspect of the court’s holding is that the state can’t tell religious people how to observe their religion. We feel that that statement is particularly important and will be important going forward.”

Rav Reisman believed filing the suit would serve several other purposes as well.

“The overall political environment was such that there was a lot of beating up on the Orthodox community, which was receiving very bad press. If you read the papers at the time, you’d believe anyone wearing a yarmulke was a religious fanatic spreading disease. I did not agree with the protests and mask-burning that was taking place, nor did most chareidei Jews. Yet the press was outrageously bunching together the behavior of all chareidim – the fight to have a minyan, along with other behavior — as one. The press and politicians were not covering our actions — so we put it out there, in a way that would certainly be noticed, that we were law-abiding citizens, wearing masks at minyan all the time, who were being targeted. And we felt that if the courts rule that we are correct that we can have minyanim, people would take notice. It would publicize this distinction, separating our issue from the behavior of some others.

“There were shuls that were following the rules, having minyanim, complying with mask requirements and, Baruch Hashem, were not COVID spreaders. Without the lawsuit, that part of the story would never have made the news.

“And finally, we understood that victory in the courts would be a mood-changer for our community. The mood in our community at the time was particularly sour. Beyond the ravages of the disease, most of us were pained and shamed by the portrayal of our religion in the national press. It was a very depressing time, for many reasons. The Supreme Court decision was a refreshing boost to our morale.”

Harav Elya Brudny, Rosh Yeshivah of Mirrer Yeshiva, was another rav who urged that a lawsuit be filed.

“There was some concern that we should keep a low profile in galus as much as possible,” Rav Brudny says. “But the consensus was that we were being persecuted, and by filing a suit, all we’d be doing is taking advantage of the system that is available to us, so we should not be concerned about eivah (hatred). Furthermore, we felt that if the Catholics bring a lawsuit and we don’t, it could be a chillul Hashem, because it would appear that they are more concerned about their prayer services than we are. We felt that we must be at the forefront of this battle.”

***

While Rav Reisman and Rav Brudny were encouraging the suit, there were some serious issues to be considered when it came to the question of whether Agudath Israel itself would be a plaintiff in the case.

“Having Agudath Israel lead the lawsuit gave it the national prominence it deserved,” Rav Reisman says. “Both within our community and on the national stage, this changed our case from a suit brought by individuals to a suit led by Orthodox Jewry’s premier organization. It became more likely that the U.S. Supreme Court would agree to review our case.”

But joining would not be without risks to Agudah and the Jewish community, as there was a real chance it could destroy what Agudah leaders say was a positive relationship between the organization and the state’s executive.

“The job of Agudas Yisrael is, regardless of who’s in office, it’s imperative that we keep good working relationships with them,” Mr. Werdiger says. “Over the years, the governor came to my house many, many times, had various meetings, had meetings with us in Albany, and in the Agudah. I thought the relationship was pretty cordial and good. We had a good working relationship with his staff. It never got that contentious over the years.”

“The only time I can recall that we were at loggerheads with Cuomo was when he was championing the redefinition of marriage,” Rabbi Zwiebel says. “We went up to Albany to lobby against it, because our gedolei Yisrael had told us that this was something we couldn’t tolerate as a society, and we had to speak out against it. He found out that we were in Albany and he sent an aide to, how shall I say, try to persuade us to think again about the position that we had taken and how actively we were pursuing it. That was a not a pleasant encounter.”

“But in general,” Rabbi Zwiebel says, “Cuomo spoke out frequently and forcefully against antisemitism, strongly displayed solidarity with Israel even during some difficult times, and opposed the BDS movement. He also supported various funding streams for the yeshivah community.”

Agudath Israel joining the lawsuit might jeopardize this relationship and incur the wrath of a governor who, for all his friendliness with the community to that point, could be a political bully. Perhaps it would be wiser if the plaintiffs were just a few shuls who didn’t have much to lose, and keep the organization that regularly lobbied state government on behalf of the Jewish community out of the crosshairs of a potentially vengeful executive?

But the rabbanim said it was important that Agudath Israel indeed join the suit, despite the risks of Agudah losing its ability to advocate on behalf of the community.

“Agudah represents Torah Jewry that is law-abiding and follows dina d’malchusa dina,” says Rav Brudny. “We always played by the rules. Our name means a lot, and a judge notices this — that these Orthodox Jews are very principled and devout and stick to Halachah, but also respect the law. That combination gives us a lot of prestige.”

***

While discussion about plaintiffs was ongoing, Mr. Schick and his team at Troutman Pepper were working feverishly. Also in on strategizing sessions were Rabbi Zwiebel and Mr. Werdiger, along with Agudah attorneys Avrohom Weinstock and Mordechai Biser; Agudah staffer Ari Weisenfeld; Rabbi Yeruchim Silber, Agudah’s director of New York government relations; and Agudah communications director Leah Zagelbaum.

It was round-the-clock work filing the brief. On Thursday morning, Rabbi Zwiebel called Mr. Schick and said, “I just got off the phone with several senior members of the Moetzes. You can file suit.”

Agudath Israel was in as a plaintiff. So were three of its shuls and their leaders: Madison and Rav Reisman; Bayswater and Harav Menachem Feifer; and Kew Gardens Hills and its secretary Steven (Shabsie) Saphirstein.

Late Thursday morning, on the fourth day of Chol HaMoed, less than 48 hours after Mr. Cuomo had announced his Cluster Action Initiative, the suit was brought in the Eastern District of New York.

***

Hoshana Rabbah is one of the holiest days of the year, when Jews generally engage in long prayer services and enjoy festive meals, in a final closure to the High Holiday period. But for the community activists, this Hoshana Rabbah would be a day spent on secular court activity.

The state’s reply brief was due by 11 a.m. Agudah had to answer almost immediately, and arguments were scheduled by phone in the early afternoon.

It was a frantic attempt by the plaintiffs to get a temporary restraining order keeping the shuls open at least until after Simchas Torah.

But it did not succeed.

Judge Kiyo Matsumoto denied Agudah’s motion. A separate suit brought by the Brooklyn Catholic Diocese before a different judge in the district was denied as well. The result was disappointing to Agudah, but not shocking, given the South Bay and Calvary Chapel precedents.

But most disturbing to the plaintiffs was Judge Matsumoto’s ruling that the harms they suffered by having the shuls closed “are not sufficient and are not irreparable,” because the plaintiffs “can continue to observe their religion but there will have to be modifications.”

“That was extraordinarily troubling,” recalls Mr. Schick, “because the whole point of Orthodox religious practice is that the modifications the world wants to push on us are not welcome, and we want to observe and worship and pray as generations prior have.”

***

Nearly as troubling for Agudah would be a phone call one of its leaders was about to receive from the governor.

Soon after Judge Matsumoto denied Agudah’s motion, Mr. Werdiger read a statement on video to Jews across the state, who would soon be celebrating a Shemini Atzeres unlike any other. Mr. Werdiger said Agudah would seek to engage in advocacy to try reach an agreeable compromise with Albany “that it doesn’t have to get to [further] litigation.” But, he said, “Rest assured, and Albany should know, that we are not finished” and will “do everything at our disposal to make sure that our rights are protected … This is not the end, we will continue.”

The video immediately went viral. And shortly thereafter, just before the start of Shemini Atzeres, Mr. Werdiger’s cellphone rang. It was Governor Cuomo. An angry Governor Cuomo.

Mr. Werdiger declines to share the exact words the governor used because “it was not a nice thing to say.” But he describes the conversation as follows: “Cuomo took it very personally. He kept referring to not only the personal relationship that we had, but also the warm relationship that he enjoyed with the Agudah, with the Jewish community, and kept on harping on that. When he saw that it was out of my hands and that I had deferred to the Rabbis, and he saw that he’s not getting anywhere, he got very irate. The governor told me that if we back him into a corner and take him on, it’s not going to bode well for us.

“I replied, ‘This is not personal. You’ve made what we felt were egregious decisions that affect our community, and the Rabbis are not going to stand by and let that happen, regardless of whether it affects our relationship or not. Prayer and studying are far more important than to maintain a relationship, and we’re going to do what we have to do.’ The governor was quite upset.”

With Mr. Cuomo having threatened Agudah, the lay leaders discussed again with their rabbanim whether they should continue with the appeals. The answer was yes.

“We felt that Agudah’s name would make a big difference in getting higher courts to take the appeals,” says Rav Brudny. “And because Cuomo was being unfair, at what point do we not have to put our foot down? Since we were proceeding within the law and the court system, we could not allow ourselves to be bullied when this affects our Yiddishkeit and avodas Hashem.”

At the time, Mr. Cuomo was flying high: Despite some rumblings about a nursing-home scandal, a Siena College poll released October 2 had shown the governor with a 59% favorability rating, a 61% job-approval rating, with 73% of voters approving of his handling of the COVID pandemic. The governor’s daily press conferences in the early months of the pandemic made him a national media star. In just a few days, he would release a book about his leadership during the pandemic, for which he’d get a $5 million advance; in six weeks, he’d be announced as an Emmy winner for his televised COVID briefings. He was seemingly on track to cruise to a fourth term in November 2022, and possibly run for the presidency after that.

What sense was there in challenging this political superstar, whom Agudah would presumably have to lobby for years to come, friends and other community members challenged Mr. Werdiger.

“Many people said to me, ‘Are you out of your mind, suing the governor?’” recalls Mr. Werdiger. “Had we lost the case, we would have had egg on our faces. But, like everything else in the Agudah, we’re somech on daas Torah.”

The lawsuit would proceed. And Andrew Cuomo would never speak with an Agudah leader again.

***

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals granted an expedited hearing for Agudah’s appeal, which was merged with the Brooklyn Catholic Diocese’s. But on November 9, the three-judge panel denied the appeal by a 2-1 vote.

In dissent, Judge Michael Park argued that the Cluster Action Initiative indeed discriminates against religion, noting that “essential” businesses are permitted to remain open in red zones with no occupancy limits.

“The Governor’s public statements confirm that he intended to target the free exercise of religion,” wrote Judge Park. “The day before issuing the order, the Governor said that if the ‘ultra-Orthodox [Jewish] community’ would not agree to enforce the rules, ‘then we’ll close the institutions down.’”

Judge Park argued that the Cluster Action Initiative was not narrowly tailored to be as least-restrictive as possible, as required when imposing limitations on First Amendment rights, citing comments by Mr. Cuomo himself that the Initiative was “not a policy being written by a scalpel,” but “a policy being cut by a hatchet.” Mr. Cuomo had made these comments in the Oct. 6 conference call with Jewish leaders, a leaked recording of which was posted exclusively on Hamodia.com and cited in court filings.

“The fixed capacity limits do not account in any way for the sizes of houses of worship in red and orange zones,” Judge Park wrote. “For example, two of the Diocese’s churches in red or orange zones as of October 8, 2020 seat more than a thousand people. But the order nonetheless subjects them to the same 10-person limit in red zones applicable to a church that seats 40 people. Such a blunderbuss approach is plainly not the ‘least restrictive means’ of achieving the State’s public safety goal.”

Mr. Schick says that, despite the loss, Judge Park’s dissent was important.

“We’d always understood that the lower courts would be a challenge, especially considering the prior rulings in South Bay and Calvary Chapel,” he says. “We were encouraged that we got a strong dissent in the Second Circuit. All along, the plan was to get to the Supreme Court with as strong a case and record as possible.”

Days after the verdict, Agudah and the Diocese filed appeals for an injunction with the Supreme Court of the United States.

A number of other cases had been filed with various federal courts around the state by Jewish and Catholic groups over the closure of schools and houses of worship. But this consolidated Agudah/Diocese case, now labeled Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, would be first to make it to the high court.

***

Former Supreme Court Justice William Brennan was said to have remarked that the most important rule in constitutional law is the “Rule of Five” — the number of justices needed for a majority ruling in the nine-member Court.

An important change had taken place at the Court since South Bay and Calvary Chapel. Those cases had been decided 5-4, with Chief Justice John Roberts, a moderate conservative, joining the four liberals for a majority ruling in favor of government pandemic restrictions that curtailed religious liberties. But on September 18, liberal legend Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had died, and President Donald Trump had replaced her with Amy Coney Barrett, who would presumably be a fifth reliable conservative. Barrett was confirmed by a Republican Senate on October 26.

But would the new justice vote to overturn two cases decided so recently, and upon which numerous lower courts had relied to uphold pandemic restrictions?

Wednesday, November 25 was Thanksgiving Eve. As business hours ended, it appeared the parties would have to wait for a verdict at least until after the long holiday weekend.

Then, at 11:48 p.m., an email from the Court hit Mr. Schick’s inbox.

He picked up the phone and dialed.

“Hello,” Rabbi Zwiebel answered.

“We won,” Mr. Schick said.

Rabbi Zwiebel nearly dropped the phone.

“It was a moment of tremendous excitement,” Rabbi Zwiebel recalls. “I’ll never forget the excitement in Avi’s voice, and how stunned I was.”

Rabbi Zwiebel’s next thought was one of regret — “What a shame that we don’t have an Agudah convention this year,” he laughs, recalling the sentiment a year later. The annual convention held on Thanksgiving weekend would have been a great place to celebrate the win, but due to the pandemic, the 2020 convention was to be held remotely, with all speeches having already been recorded. Rabbi Zwiebel joked to Mr. Schick, “Let’s go find a nice shul somewhere and get together and have an Agudah convention and celebrate this victory.”

“But as Rav Hutner, zt”l, used to say, ‘Ruba d’ruba feert dach di Eibeshter di velt,’ and if Hashem is running everything, this is when it was supposed to happen,” Rabbi Zwiebel says now. “This was a vindication of some very difficult months and difficult decisions that we had to make.”

“Even in a pandemic, the Constitution cannot be put away and forgotten,” read the Supreme Court ruling granting the plaintiffs a preliminary injunction. “The restrictions at issue here, by effectively barring many from attending religious services, strike at the very heart of the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty.”

Justice Barrett had indeed joined the four veteran conservatives, giving Agudah and the Diocese five votes.

***

As Mr. Cuomo had intimated to Mr. Werdiger on the Hoshana Rabbah call, Agudath Israel was dead as far as the governor was concerned.

On Sunday, October 18, Mr. Cuomo held another conference call with leaders of various Orthodox communities. This time, Agudath Israel members were not invited. Months later, when the governor scheduled a visit to a New York City yeshivah, no one from Agudath Israel was included on the guest list. (The visit was ultimately canceled due to a Cuomo scheduling issue.)

Agudah did attempt to reestablish a relationship with the administration.

“Every single public statement we put out at every stage of the appeal,” Rabbi Zwiebel notes, “we always would end with something like, ‘We look forward to continuing an ongoing relationship for the benefit of the community.’ But those sentences were not taken very seriously by the governor.”

“It was obvious that we were on the no-fly list,” says Mr. Werdiger. “In consultation with members of the Moetzes and gedolim who were involved in the original decision, after a couple of months, I did start having a conversation about possibly finding a way to extend an olive branch and to try to build back a relationship a little bit, for the sake of the Agudah. But then everything imploded, and we dropped that conversation.”

Everything indeed imploded for Mr. Cuomo, quickly and stunningly, as he became engulfed in multiple scandals in rapid succession.

An order he had signed early in the pandemic mandating that nursing homes accept COVID patients from hospitals was subsequently blamed for the deaths of thousands of nursing-home residents. His administration then was accused of trying to cover up the true number of nursing-home fatalities — a number it released only when publicly called out by Attorney General Letitia James. The debacle led the Legislature to sharply curtail the governor’s emergency powers. Mr. Cuomo was criticized for writing a book during the pandemic, and using state employees to help write it. Finally, facing certain impeachment after being accused of harassing multiple staffers, a disgraced Andrew Cuomo resigned the governorship in August, and was replaced by Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul.

***

Lower courts and governments throughout the nation would now be relying on the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Agudah/Diocese case, which essentially overturned South Bay and Calvary Chapel and established new precedent for injunction cases during the pandemic. The ruling has been cited more than 200 times.

The case on the merits went back to lower courts, labeled Agudath Israel v. Cuomo. After another round of briefing and argument, a unanimous Second Circuit issued a statewide permanent injunction nullifying the Cluster Action Initiative. The Second Circuit ruling established that — in contrast to Judge Matsumoto’s decision on Oct. 9 — when religious liberties are violated, irreparable harm is presumed. The ruling has been cited more than 40 times.

Mr. Cuomo, once virtually assured of a fourth term in office, was gone before the end of his third.

And months after he left office, the Jews who had so antagonized him with their lawsuit received further vindication.

Attorney General James, who is now among those challenging Ms. Hochul for the gubernatorial seat in 2022, had appointed special investigators last spring to probe the various allegations against Mr. Cuomo. Among those interviewed was Dr. Elizabeth Dufort, who had served as medical director of the state Health Department’s epidemiology division during the pandemic, before resigning in December. Transcripts of the investigators’ interviews were released this month.

Ms. Dufort’s testimony painted a picture of a pandemic response tightly controlled by the Executive Chamber, rather than Health Department medical officials, despite Mr. Cuomo frequently saying policies are dictated by “the science and the data.”

When an investigator asked Ms. Dufort whether the Executive Chamber ever issued instructions “that went against the professional judgement of Health Department employees,” she replied, “The zones were very complicated. There were metrics that our staff would work on, but they would only be announced that people met the metrics if that came from the Chamber. Some areas met the metrics and would be called a zone and others met the metrics and would not be called a zone.”

Ms. Dufort continued, “Our staff, who worked for hours and hour on these metrics and then nothing would be announced, and it was very unclear as to why. They would get very frustrated. And for me that was part of my not wanting to be involved in a lawsuit about the metrics without having clarity on how they were established.”

The lawsuit Ms. Dufort was referring to was almost certainly the Agudah/Diocese case.

When the state filed its reply brief on the morning of Oct. 9, 2020, the brief had approximately 19 citations to a “Dufort Declaration.” But Mr. Schick never got a “Dufort Declaration” — the actual declaration he eventually received was a “Zucker Declaration,” signed by Health Commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker. (And the state’s amended brief replaced references to the “Dufort Declaration” with the “Zucker Declaration.”)

In her interview with investigators, Ms. Dufort discussed an instance in which a person or persons in the administration were upset she was going on vacation in October. She was confused as to why they were giving her trouble about the vacation; it turned out they wanted her available as an expert witness for a lawsuit.

(Portions of the transcript that were blacked out before being released are indicated here by X’s. From the context of the interview, and the size of the blacked-out portions, it appears that these redactions are possibly covering up the word “red zone,” though the word “red zone” appears unredacted in other places.)

“I was confused that it was about a lawsuit … and they wanted me to be available as an expert witness, although I had never even known what a XXXX was,” Ms. Dufort said. “I had not been in one meeting or call or invite or verbal or written anything about what a red zone was. I only knew what it was through the New York Times. So I was really perplexed why this was felt to be solely my responsibility.”

“I think that they were looking for someone to be an expert witness on that case and some people as I understood it were refusing to go do these legal attestations or affidavits. Some had resigned and were no longer available to do that and their positions were left empty or replaced with people without expertise. I think part of the challenge was the system of not having other experts willing to do it, but even if I had been available I would not have done it. I didn’t know how they determined a XXXX and no one that I worked closing [sic] with knew how they determined a XXX, what the metrics for — at that time how they determined it.”

“When you say how they determined the XXXX, who is they?” asked the investigator.

“The Chamber,” replied Ms. Dufort.

For the Jewish community, the Dufort testimony was further vindication that they had been targeted for shutdown by the governor, who was not following science or data but acting unilaterally under emergency powers. It appeared to show that political forces, not medical professionals, had written the declaration used by the state in its October 9 filings. The administration had seemingly sought to give the declaration an air of medical professionalism by having the state’s chief epidemiologist sign it; when she — and perhaps others — had refused, it was ultimately signed by Commissioner Zucker, a political appointee.

When Hamodia asked a Cuomo spokesperson, shortly after the Cluster Action Initiative was announced, why the governor had told the Jewish leaders to keep the shuls at 50% capacity just hours before limiting them to 10 people, the spokesperson replied, “We were still in discussions with the epidemiologists at the time and they made clear that preventing large social gatherings is the key to breaking up these clusters.” But if Dufort’s testimony is to be believed, the zones were not made by the epidemiologists after all.

“There was no rhyme or reason to the zones,” says Mr. Schick, “which was a source of great frustration to the community, all along. How could it be that this neighborhood has a certain metric and that designated red, but another neighborhood in a different county could have much higher numbers, and nothing?

“Well, not only did it offend us, but it turns out it had offended the state’s chief epidemiologist, which was nice to hear.”

A Cuomo spokesperson did not respond to Hamodia’s request for comment on this article.

***

To those who fought the battle for religious liberty one year ago, the victory, and the fight itself, represents something more than just one case in which religious groups defeated a governor who had deemed prayer service unessential.

“One day, I want the world to think of Agudath Israel v. Cuomo not only as a famous case in the history of religious-freedom cases that were brought to the Supreme Court, but about a lifestyle,” says Rabbi Zwiebel. “They would think about the way we comport ourselves. Cuomo comported himself in ways which were demeaning to women, which were abusive in terms of power relationships that he had with other people. The community of Agudas Yisrael, which is subservient to daas gedolei Yisrael and conducts itself in interpersonal ways in our culture of tznius, which is something very beautiful and very powerful — that they will think of that when they think about Agudath Israel v. Cuomo.”

“For those who are in positions of leadership in the frum community, this is a reminder that almost everything that we do, and everybody we interact with, are temporary,” says Mr. Schick. “The only permanent one is the One Above, so we might as well throw in our lot with Him, and do what’s right lichvod Shamayim.”

—

rborchardt@hamodia.com

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.