The Israeli Electoral System De-Mystified

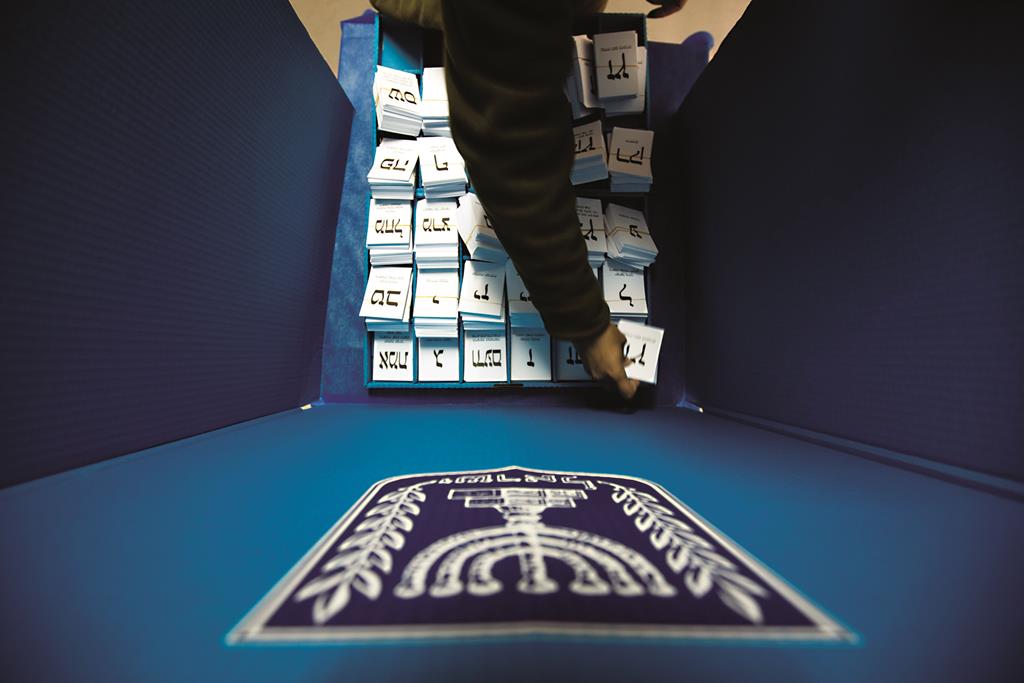

The citizens of “Start-Up Nation” cast their votes by hand. After presenting their voting credentials to the poll officials, they stand behind a cardboard partition, where they select a ballot slip bearing the initials of the party of their choice, and insert the slip into a slit in a blue ballot box.

The low-tech process continues as the votes are later counted by hand and then phoned in to the Central Election Office, which compiles the nationwide tally. While it is admittedly a slow, laborious process, it does avoid some of the traumas inflicted on Americans by technological advances in recent years, such as hanging chads and Election Day computer crashes and hacking perils. Vigilant human vote counters, poll watchers and police are on hand throughout to discourage vote tampering and intimidation. But there are no guarantees.

It is it at this point that the mystery begins of how those votes, several million of them, are then apportioned in the form of seats according to party affiliation in the 120-seat Knesset.

Actually, there is no mystery, but the complexities of the Israeli parliamentary system do tend to baffle Americans, who are used to voting directly for candidates for public office. We will try to make the story as clear (and painless) as possible:

Each party that passes the electoral threshold (receiving 3.25 percent of the overall vote count — an increase from 2 percent in 2013) is entitled to one or more seats in the 2oth Knesset. All the votes are divided by 120 to determine how many seats each party gets.

A party’s surplus votes, which are insufficient for an additional seat, can be transferred to another party according to agreements made between them prior to the election. If no agreement exists, the surplus votes are distributed according to the parties’ proportional sizes in the elections.

In the current elections, such agreements were signed between the Zionist Camp and Meretz, between United Torah Judaism and Shas, between Jewish Home and Likud, and between Kulanu and Yisrael Beitenu.

This year, due to the closeness of the race, the winners will likely not be known until Wednesday morning, several hours after the polls close at 10:00 p.m. Tuesday night. Complete results, including apportionment of seats after all the calculations, invalidations and recounts have been made, may not be available for days or even weeks.

But now comes the stage all have been waiting for — the choosing of a new prime minister and his cabinet. All elected parties are invited to recommend a candidate for prime minister to the president, currently Reuven Rivlin. They can recommend the head of any of the elected parties, including their own. Based on their recommendations, the president is empowered to designate one of the candidates — usually but not necessarily from the party that received the most votes — to form a majority of Knesset members for the next government.

Since none of the parties in Tuesday’s election could expect to win 61 seats (none will get even half that, according to all the polls), some combination, or coalition, of parties will have to be created.

The candidate tapped by the president is granted 42 days to form a coalition (28 days plus a 14-day extension the president can give). If the candidate fails to win the support of at least 61 MKs in that time, the president can turn to another candidate to assemble a coalition.

It is in this stage that the notorious “horse trading” takes place, in which the various parties bargain for places in the coalition in return for certain coveted cabinet seats, parliamentary chairmanships or promises of support for their favored agendas.

The 5,883,365 Israelis registered to vote could do so in one of 10,119 locations, of which 2,500 have wheelchair access. Unlike in the U.S. and Britain, Israelis in prison are allowed to vote, and 255 ballot boxes have been set up in hospitals around Israel.

This article appeared in print on page 6 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.