Politicians and Advocates Push to Keep Jewish Iraqi Archive in U.S.

A bipartisan Senate resolution urges the State Department to revisit an agreement to return a trove of thousands of sefarim and manuscripts, including those of the Ben Ish Chai, and other items seized from the Iraqi Jewish community, to the Iraqi government.

Controversy over legitimate ownership of what has become known as the Iraqi Jewish Archive dates back many years, with activists and politicians long advocating that the collection, captured by U.S. forces during the Iraq War, should remain in America or Israel, where it can be accessible to scholars and Iraqi Jews. Now, as the deadline of a previously agreed upon return date of September draws nearer, the resolution calls for a permanent solution to the dispute.

“This personal and irreplaceable trove of Jewish artifacts still belongs where they can be preserved and accessed by the Jewish community and scholars, not returned to Iraq,” said Senator Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.), one of the resolution’s co-sponsors. “These invaluable cultural treasures, like a prayer book and Torah scrolls, belong to the people and their descendants, who were forced to leave them behind as they were exiled from Iraq. The State Department should make clear to the Iraqi government that the artifacts should continue to stay in the United States.”

The resolution is co-sponsored by Senators Pat Toomey (R-Pa.), Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and closely mirrors a 2014 resolution that was passed unanimously.

Carole Basri, an adjunct professor at Fordham Law School and Jewish refugee advocate, has been a leading advocate of preventing the Archive from returning to Iraq. She told Hamodia that while she doubts it would be adequately preserved there, the matter goes beyond practical concerns and is a simple question of rightful ownership.

“There is a bigger problem here of property expropriation,” she said. “From the 1940s and on, the Iraqis made it increasingly impossible for Jews to live in the country and, when they fled, they were not allowed to take anything with them; the state seized everything. It does not seem fair that now, the little bit of cultural heritage that survived should also be taken away from us.”

A spokesman for the State Department told Hamodia that they are engaged in negotiations with the Iraqi government and other stakeholders to extend the collection’s stay in the U.S., but did not comment on whether keeping it in the country on a permanent basis was a goal.

The saga of the Archive dates back to 2003, when a group of American soldiers found it in the flooded basement of Iraq’s intelligence agency. The items were initially identified as a significant find by Harold Rhode, a Jewish Pentagon official who was in Baghdad at the time together with U.S. forces. After a cursory inspection of the items, an agreement was made with the provisional Iraqi government that the Archive would be transferred to America for study and restoration, but that it would be returned to the country at a later date.

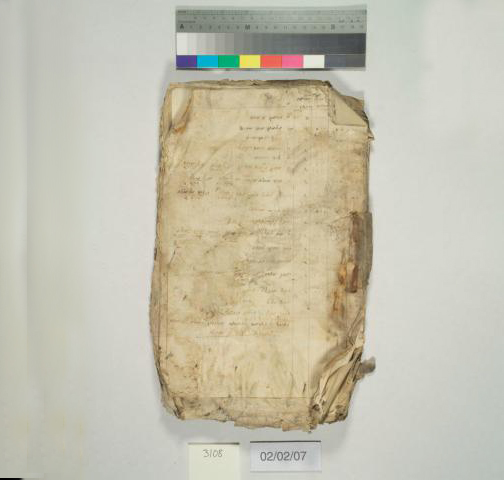

The collection of 2,700 sefarim, along with thousands of other assorted documents that had been seized from shuls, Jewish schools and various communal bodies, was given to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), which invested some $3 million in restoring and digitizing the collection. In the process of their work, they identified a Chumash dating back to 1568, as well as Mishnayos, Zohars, Gemaros and other sefarim from the 18th and 19th centuries. Several items have been put on display in museums around the country and, in 2013, many fragments from sifrei Torah and other irreparable items were buried in New Montefiore Cemetery on Long Island.

Soon after the value of the collection’s contents became known, several U.S. officials questioned whether the original condition to return the items to Iraq should be honored. Over the last 15 years, deadlines for return have been postponed several times. In 2013, representatives of the Iraqi government signaled that they would be open to allowing the Archive to remain in the U.S., but after elections brought in a new government, demands for its return were renewed.

“They [the Iraqi government] say that they want it back to teach their people about the ethnic groups that lived there, but they have never presented an official plan for how they would protect it, and if they are so concerned with Jewish heritage, then why are they still keeping over 300 Torahs decaying in the damp basement?” asked Gina Bublil-Waldman, President of Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa (JIMENA), which has led efforts to publicize the campaign to prevent the Archive from returning to Iraq.

The sifrei Torah in her statement refer to reports of some 365 scrolls kept in the vault of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

Many of the items in the Archive were seized from a Baghdad shul by the government of Saddam Hussein in 1984. They had been placed there for safekeeping by thousands of Iraqi Jews who fled the country amid severe persecution in the 1940s and 1950s. Between 1950 and 1952 alone, 130,000 members of the community, which had been present since the destruction of the First Beis Hamikdash, fled. As repressive and dangerous conditions continued, with frequent arrests and executions — often on trumped-up charges of spying for the State of Israel — more continued to leave through the coming decades, forced by harsh laws to leave most of their possessions behind.

“They [Iraqi Jews] left empty-handed to whatever country would take them, and now you find out that they have a siddur that your grandfather prayed with and Iraq wants to make that government property. By what right do they deserve this?” said Mrs. Bublil-Waldman.

In addition to the thousands of sefarim, the Archive contains thousands of writings and letters from Iraqi Rabbanim and communal leaders, as well as documents from schools and Jewish institutions.

While most of the items in the Archive are communal property, Mrs. Basri claims that much of it is private property of her family, which operated a school in Baghdad for many years.

“My grandfather opened a school for the Jewish kids who could no longer go to public school, and it was the only one that stayed open after 1967. He never gave up ownership, and half the Archive comes from the school; it’s our family’s property,” she said.

A request for comment to Iraq’s Washington embassy from Hamodia as to what their plans would be for the Archive if it were returned and whether they would agree to postpone the return date went unanswered.

Besides issues of preservation and ownership, many advocates say that the huge collection has yet to be thoroughly investigated by rabbinic scholars familiar with the significance of some of the texts and manuscripts. Due to the sheer size of the Archive, many items have yet to be identified and catalogued. As NARA began to publicize its work on the Archive four years ago, scholars working for the Brooklyn-based Sephardic Heritage Museum recognized in one of the images what appeared to be the handwriting of the Ben Ish Chai, who had been the spiritual leader of Baghdad’s community until his petirah in 1909. The museum’s director, Rabbi Raymond Sultan, gained access to the collection and confirmed that these were indeed writings of the great Gaon of Sephardic Jewry. The discovery resulted in the publication of two sefarim of commentary on Chumash and a third soon to be released of drashos and halachic responsa — all of which is previously unknown Torah from the Ben Ish Chai — titled Birchas haReiach.

“It took a whole team to work with the manuscripts, which were written in an old Sephardi script that is not used anymore,” Rabbi Sultan told Hamodia. “I don’t know if we will find anything else like this, but there probably are other important documents to find, and if the financing can be raised, it would be our pleasure to publish them.”

Advocates involved in the issue are largely confident that the Archive will remain in the U.S. past the September deadline, but were eager to establish a long-term plan that would settle Iraqi claims to the collection and would arrange for it to be housed in a location in either the United States or Israel, where large populations of Iraqi Jews reside.

“This Archive is part of the story of a million Iraqi Jews who had their heritage stolen from them,” said Mrs. Bublil-Waldman. “This goes beyond the local issue with Iraq; it sets an important precedent for many ongoing struggles over property between Jewish communities from Arab lands — the countries that threw them out and now want to claim their heritage.”

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.