Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s First Black President, Dies

Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first black president, spent nearly one-third of his life as a prisoner of apartheid, the system of white racist rule that he described as evil, yet he sought to win over its defeated guardians in a relatively peaceful transition of power that inspired the world.

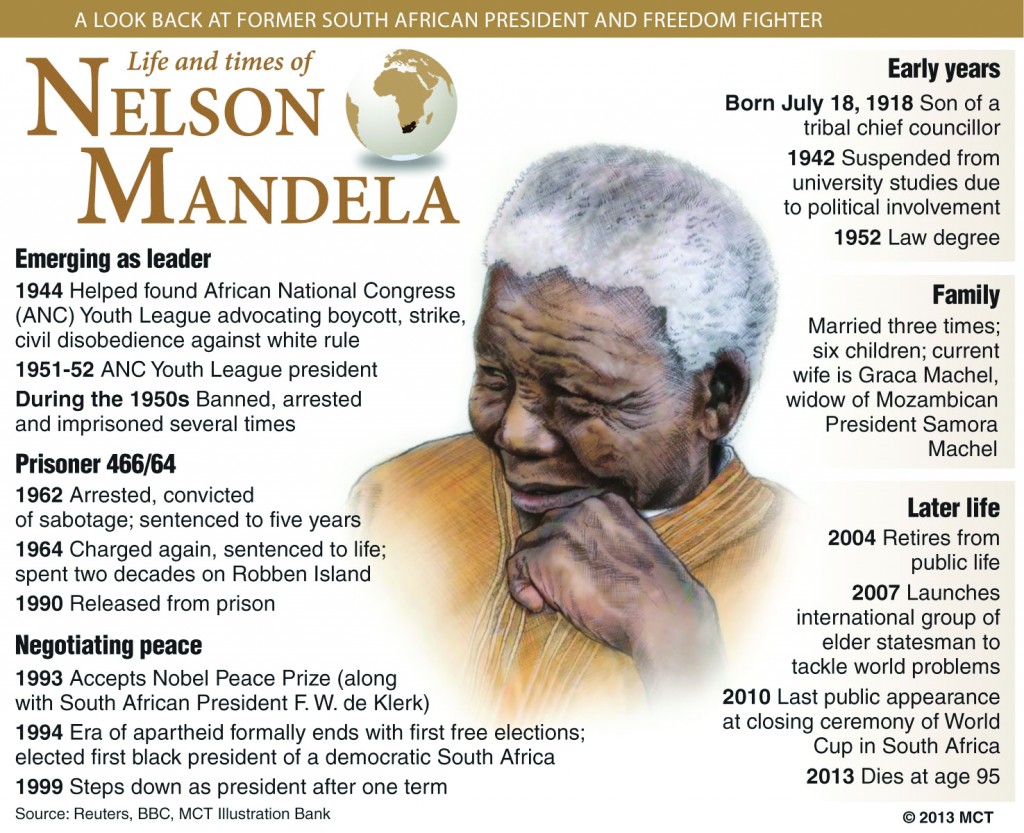

Mandela died on Thursday at the age of 95.

South African President Jacob Zuma made the announcement at a news conference late Thursday, saying, “We’ve lost our greatest son.”

Mandela’s stature as a fighter against white racist rule and a seeker of peace with his enemies was on a par with that of other men he admired — American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. and Indian independence leader Mohandas K. Gandhi, both of whom were assassinated while actively engaged in their callings.

In the 1950s, Mandela sought universal rights through peaceful means but was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1964 for leading a campaign of sabotage against the government. The speech he gave during that trial outlined his vision and resolve.

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people,” Mandela said. “I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

He was confined to the harsh Robben Island prison near Cape Town for most of his time behind bars, then moved to jails on the mainland. It was forbidden to quote him or publish his photo, yet he and other jailed members of his banned African National Congress were able to smuggle out messages of guidance to the anti-apartheid movement, and in the final stages of his confinement, he negotiated secretly with the apartheid leaders who recognized change was inevitable.

Thousands died or were tortured or imprisoned in the decades-long struggle against apartheid, which deprived the black majority of the vote, the right to choose where to live and travel, and other basic freedoms.

Thousands died or were tortured or imprisoned in the decades-long struggle against apartheid, which deprived the black majority of the vote, the right to choose where to live and travel, and other basic freedoms.

So when inmate No. 46664 went free after 27 years, people around the world rejoiced. Mandela raised his right fist in triumph, and in his autobiography he would write: “As I finally walked through those gates … I felt, even at the age of seventy-one, that my life was beginning anew.”

Mandela’s release rivaled the fall of the Berlin Wall just a few months earlier as a symbol of humanity’s yearning for freedom, and his graying hair, raspy voice and colorful shirts made him a globally known figure.

Life, however, imposed new challenges on Mandela.

South Africa’s white rulers had portrayed him as the spearhead of a communist revolution and insisted that black majority rule would usher in bloody chaos. Thousands died in factional fighting in the run-up to democratic elections in 1994, and Mandela accused the government of collusion in the bloodshed. But voting day, when long lines of voters waited patiently to cast ballots, passed peacefully, as did Mandela’s inauguration as president.

“Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world,” the new president said. “Let freedom reign. The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement! G-d bless Africa! Thank you.”

Since apartheid ended, South Africa has held four parliamentary elections and elected three presidents, always peacefully, setting an example on a continent where democracy is still new and fragile.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born July 18, 1918, the son of a tribal chief in Transkei, a Xhosa homeland that later became one of the “Bantustans” set up as independent republics by the apartheid regime to cement the separation of whites and blacks.

Mandela’s royal upbringing gave him a regal bearing that became his hallmark. Many South Africans of all races would later call him by his clan name, Madiba, as a token of affection and respect.

Mandela began his rise through the anti-apartheid movement in 1944, when he helped form the ANC Youth League.

He organized a campaign in 1952 to encourage defiance of laws that segregated schools, marriage, housing and job opportunities. The government retaliated by barring him from attending gatherings and leaving Johannesburg, the first of many “banning” orders he was to endure.

After a two-day nationwide strike was crushed by police, he and a small group of ANC colleagues decided on military action, and Mandela pushed to form the movement’s guerrilla wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation.

He was arrested in 1962 and sentenced to five years’ hard labor for leaving the country illegally and inciting blacks to strike.

A year later, police uncovered the ANC’s underground headquarters on a farm near Johannesburg and seized documents outlining plans for a guerrilla campaign. At a time when African colonies, one by one, were becoming independent states, Mandela and seven co-defendants were sentenced to life in prison.

The ANC’s armed wing was later involved in a series of high-profile bombings that killed civilians, and many in the white minority viewed the imprisoned Mandela as a terrorist. The apartheid government, meanwhile, was denounced globally for its campaign of beatings, assassinations and other violent attacks on opponents.

Mandela’s final years were marked by frequent hospitalizations as he struggled with respiratory problems that had bothered him since he contracted tuberculosis in prison.

He stayed in his rural home in Qunu in Eastern Cape province, where Hillary Clinton, then U.S. secretary of state, visited him in 2012, but then moved full time to his home in Johannesburg so that he could be close to medical care in Pretoria, the capital.

He is survived by Machel; his daughter Makaziwe from his first marriage, and daughters Zindzi and Zenani from his second.

This article appeared in print on page 1 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.