French Policy Challenged in Families’ Battle for Kvod Meisim

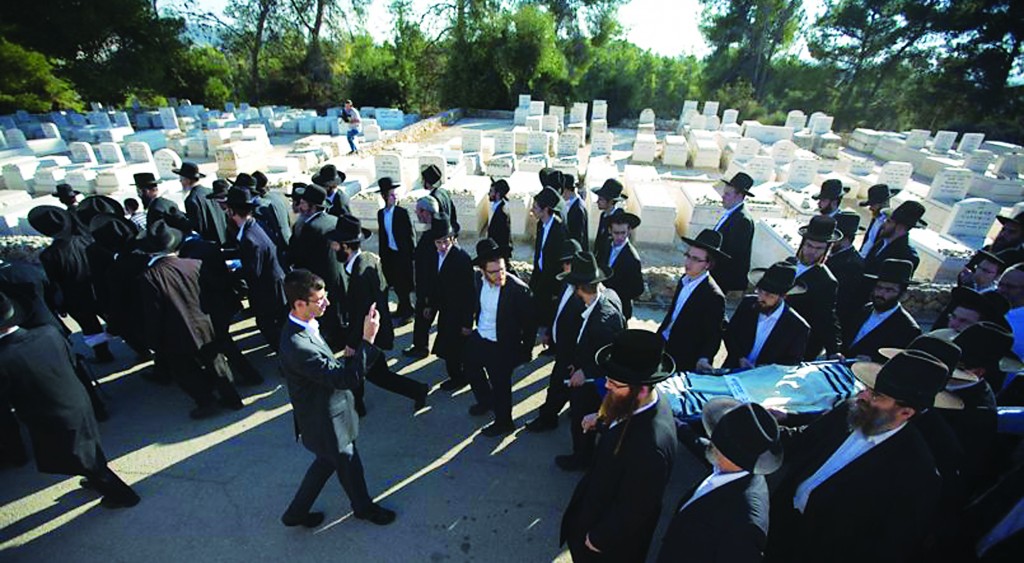

In what could prove to be a watershed case impacting the very viability of French Jewry, the remains of Giacomo (Yaakov) Tedseco and his wife Therisa (Yirat) Tedseco were escorted with a sizeable levayah from Paris this past Thursday October 24 to be flown to Eretz Yisrael. The niftarim were reinterred in the Artsos Hachaim Bais Olam in Beit Shemesh on Monday, October 28.

Space is at a premium all over Europe. There are no privately owned cemeteries in France. All burial plots in the country are owned by municipal governments. In order to maximize the “efficiency” of burial grounds and to prevent their expansion, an arcane law was passed long ago granting municipalities the right to exhume human remains 100 years after interment. Obviously, as halachah (Yoreh Deah 363) demands that Jews rest in their kevarim until techiyas hameisim and that such pinuy hameis, especially when it causes remains to be left without in-ground burial, is a bizuy hameis. This law makes dying, and therefore living, in France an unsustainable plan for halachah-observant Jews.

Giacomo-Yaakov Tedesco was born in Venice, Italy on August 27, 1799. He immigrated to France as a 20 year old; miraculously surviving for 20 hours in the water before reaching the French coast after the ship transporting him from Italy sank.

The life Giacomo built for himself in France was nearly as miraculous as his entry into the country. He settled in Paris and on June 12, 1833/25 Sivan he married Therisa (Yirat) nee Cerf (Scharf). They raised a family of 11 children together. That same year, he opened an art supply store. Mixing kindness with business he would often give struggling artist supplies for free. In return, they would give him their artwork to sell. As a result, his humble art supply store became a famous art gallery, Tedesco Freres. It remained a family business until the Nazi occupation in 1941. The generosity Giacomo first extended to young artistes would manifest itself in many ways in the future.

Having amassed considerable wealth, valuable connections and influence through Tedesco Freres, he marshaled all his faculties and resources for Torah, avodah and gemilus chassadim.

Among many other philanthropic activities and tzarchei tzibbur, he built the first modern mikveh in Paris that remained in use until WWII, the first Orthodox shul (which is still in existence today), currently called the Rue Cadet Shul-Adass Yereim, and the first kosher butcher shop. He was a mohel and one of the founding members of the Chevrah Shas in Paris which studied the entire Shas over 25 years and made their first siyum haShas in 1867. Quite possibly, this was the first public, communal siyum haShas ever.

In an era when the Reform had won over almost all of French Jewry, Yaakov Tedesco was an ehrliche Yid and a staunch opponent of the Reformers. So much so that he only chose shidduchim for his 11 children from among the families of Orthodox German Rabbanim. He was a mechutan of Harav Samson Raphael Hirsch, Harav Ding and Harav Bamberger, the Würzburger Rav, among others.

Yaakov Tedesco was niftar December 11/17 Kislev, 1870 while Paris was under siege during the Franco-Prussian war and was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. As curator of a major art gallery, philanthropist and communal activist his passing received notices in major European newspapers and his initial levayah was the type of kvod acharon that befits a larger-than-life personality.

For most people their kvod acharon is when their Olam Hazeh stories end. But for the tenacious, dedicated descendants of Giacomo Tedesco, for whom kvod ha’adam, kvod avos and kvod Shamayim were of paramount concern, Giacomo’s burial in Montparnasse Cemetery is where the story begins.

The French capital has a long, enigmatic and macabre history of disinterment and reburial and a very cavalier attitude toward the sanctity of human remains.

The now defunct Holy Innocents’ Cemetery (French: Cimetière des Innocents) was located in the center of Paris and was used from the Middle Ages until the late 18th century. In the 14th and 15th centuries, to relieve the overcrowding of the mass graves in Cimetière des Innocents, Parisians built arched structures called charniers or charnel houses along the cemetery walls and bones from the graves were dug up and deposited in them. Owing to health concerns, this ancient burial ground, along with 10 more of the city’s overcrowded cemeteries, were closed just before the French Revolution and the bones of over six million deceased Parisians were transferred to what are now known as the Catacombs. Cemeteries were then banned from the Paris city limits.

In 1824 the Montparnasse Cemetery (Cimetière du Montparnasse) originally known as Le Cimetière du Sud (Southern Cemetery) was created from three farms. At the time these farms were well outside the precincts of the capital. In fact some of the new “suburban” cemeteries were so distant at the time that the graves of several famous French men and women were moved to them to make them more popular with the bourgeois Parisians.

Only the city is authorized to sell plots; they cannot be bought and sold between individuals like property. Plots can be purchased for 10, 30, or 50 years with the option to renew, or “en perpétuité” (forever).

Despite the fact that Giacomo Tedesco purchased his family plot in-perpetuity, the Paris municipal government exercised its legal right to disinter remains after 100 years and removed the bones of the Tedescos to the ossuary at Pere Lachaise where they were kept in drawers in an underground vault. Mrs. Therisa (Yirat) Tedesco, who died in 1867, was disinterred in 1999. Her remains had been without kever Yisrael for 14 years and her husband, who died in 1870, was disinterred in 2002. His remains had been without kever Yisrael for 11 years.

Before the disinterment, the Paris municipality drafted a letter apprising the recipient of their plan. Ludicrously, the letter was sent to where the records indicated next-of-kin would be living at a non-existent address! When the first letter was, unsurprisingly, returned unopened it was re-sent to a descendant of the chevrah kaddisha — who may or may not have been Jewish but who, in any event, did not respond. With this tacit “approval” of the responsible parties the municipality proceeded to break the matzeivah, remove the aron and move the contents to the ossuary. Curiously, bones of two other people were discovered in the aron containing Giacomo Tedesco’s remains and this would contribute to the bureaucratic boondoggle that was to follow.

The actual descendants of the Tedescos were finally apprised of this tragic bizuy hameis in 2008. A great-great-granddaughter of the couple, Dr. Debbie Lipshitz nee Wechsler, PhD. had been on a trip to Paris from Eretz Yisrael when she went to visit her grandparents’ kevarim at the Montparnasse Cemetery. Once there, she decided she would go to the kevarim of their grandparents as well. It was then that, to her horror, she discovered the empty graves.

The saga that then began and that culminated successfully in Beit Shemesh on Sunday, was a bureaucratic, red-tape nightmare of Kafkaesque dimensions. It truly deserves a full book-length treatment but the salient points are as follows:

Through a frum local attorney, Alex Buchinger, Esq., the family brought a suit against the city of Paris for the release of the Tedesco remains from the Pere Lachaise ossuary. The official response was that the remains could no longer be moved anywhere without written consent of all descendants! If those family members suing for reinterment in Israel could not prove that some descendants were deceased they would have to obtain their signatures of consent. Six surviving great-grandchildren of the Tedescos then engaged the services of a German genealogist who was able to trace over 1,000 descendants of Giacomo and Therisa Tedseco. To obtain and transmit close to 1,000 birth and death certificates was impossible.

Even after relenting on this impossible demand, the Parisian authorities insisted that the presence of the unknown bones in Giacomos aron demanded that, whoever they were, their next-of-kin must also authorize relocation of their remains in writing. However, confidentiality laws prevented the municipality from identifying these remains for Dr. Lipshitz and for Mrs. Yehudis Weiss of Kensington, Brooklyn, two great-great granddaughters who were fighting tenaciously on their ancestors’ behalf.

Harav Shmuel Wosner, shlita, was matir DNA testing in this case to allow for positive identification of the remains. But the process is slow, involves bone scrapings (further bizuy hameis) and the costs are astronomical. Noting infant mortality rates in the mid-19th century Mr. Buchinger argued to the authorities that in all likelihood the unidentified remains in Giacomos aron were those of his children or grandchildren. Ultimately they accepted this argument but were still stubborn about the written consent.

Many Parisian askanim were reluctant to get involved in the case. Considering the current chilly state of affairs between the French government, French Jewry and the Israeli government, they felt that they must pick their battles and that these battles were best left in advocating for the rights of the living rather than for the dignity of the dead.

Dr. Sharbit of Paris and Mrs. Dreyfus of the Agudah in Antwerp, Belgium were local and regional askanim who advocated vigorously on the families’ behalf. They have gone so far as to lobby the European Union to pass new pan-European laws that would supersede any local laws that deny the dignity of the dead as defined by Orthodox- Jewish tradition.

While there is guarded optimism that the EU will pass such legislation in the future, Dr. Sharbit of Paris and Mrs. Dreyfus also became frustrated by the stonewalling of the Paris municipalities, the by-the-book obstinacy and inflexibility. Even after they relented on identifying the “extra” bones two weeks before Rosh Hashanah, they demanded proof that the deceased Tedescos would have wanted to have their remains reburied.

At this point Dr. Sharbit phoned Mrs. Weiss and told her that “we now need help from America.” Then, the day after Rosh Hashanah a miracle occurred and the Chief of Police in Paris called the family and informed them that they could remove the Tedesco remains for reinterment in Israel.

The entire episode has sent shock waves through the French Jewish community. They are filled with anxiety over the future of their own and their loved ones remains. One hundred years after 120 will these batei chomer that once house holy Yiddishe neshamos be relegated to a drawer in an ossuary or even to cremation?

Many notables besides the Tedescos are buried at Montparnasse Cemetery, among them Alfred Dreyfus of the infamous anti-Semitic Dreyfus affair. A good question for the Paris municipality to consider even in the absence of new EU legislation is this: Colonel Dreyfus was buried in 1935. In 2035 will his bones be disinterred as well?

It is noteworthy that when reporting about the levayah in Beit Shemesh, the French newspaper La Figaro described it as “repatriation” to Israel. This, despite the fact that Giacomo Tedesco immigrated to France from Italy and was of German extraction. The word Tedeso means “German” in Italian; in his kesubah his name is written as Yaakov Ashkenazi.

Perhaps one silver lining to this tragic yet heroic story is some sort of de facto recognition by a major player in geopolitics that Jews belong to Eretz Yisrael and that Eretz Yisrael belongs to Jews.

This article appeared in print on page 1 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.