From Ashes to ‘Art’

When I arrived at Majdanek, what first caught my eye was a huge block of engraved white stone. It introduced me to the fact that this is no longer a death camp; it is now the “Memorial Museum” of Lublin, Poland.

Standing outside the death camp, I found myself in the city of Lublin. How can it be? A death camp, so close to the center of town? People sat on their porches and saw what was going on? They weren’t bothered? The smell of burning Jewish flesh didn’t disturb their picnics? How did they carry on with their lives, just inches from a busy, efficient death camp?

I was in Majdanek twice; both times it was cloudy. The clouds hung very low. They were heavy with rain, or maybe tears.

I walked inside and what shocked me was that everything seems the same. Nothing has changed. The place seems almost in a state of readiness, about to open for business, G-d forbid. There are the barracks, and the watchtower, and the barbed wire.

Inside Majdanek is a domed structure, and under it is a pit. The pit is filled with human ashes, and fragments of human bone. When I realized what I was looking at, my blood turned to ice. How can it be that these people never merited to be buried? Not even 70 years later?

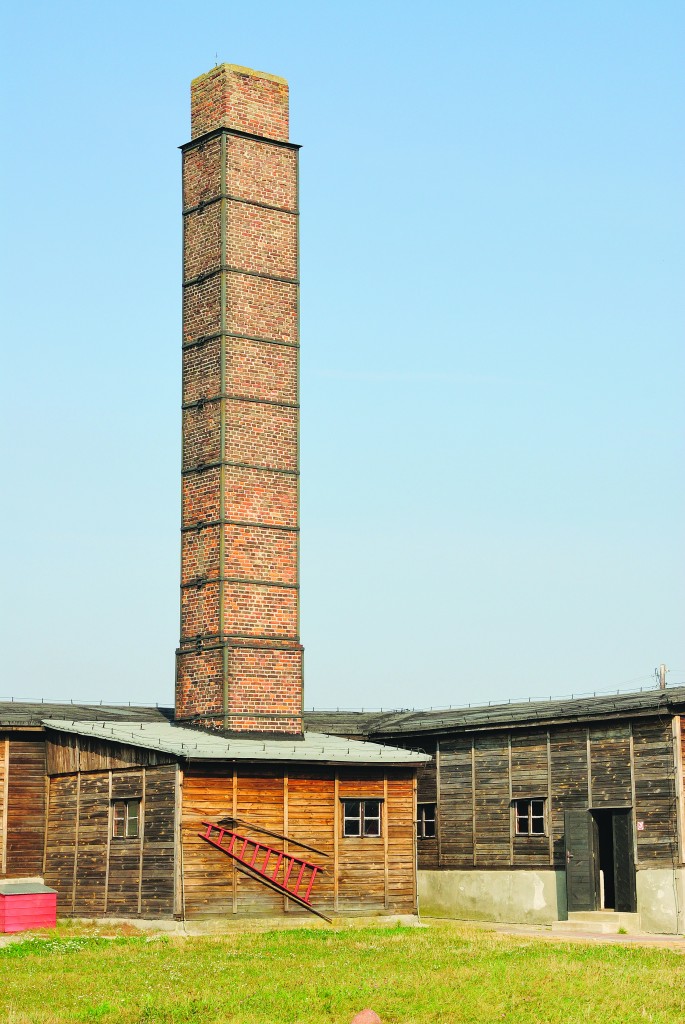

Next to the pit is an isolated building with a chimney reaching into the sky. It looks innocent on the outside. What is this chimney? What is this building? I walked inside, and I saw them. The ovens. All clean and shiny and, it seems, in good repair.

History books tell us Majdanek was considered one of the worst death camps, in terms of cruelty to prisoners. On one day in Majdanek (November 3, 1943), the Nazis shot 18,400 Jews and then ground their bodies into fertilizer, as blaring music was played to hide the screams.

And today? Seventy years later?

Today we have a Swedish artist named Carl Michael Hausswolf, who says he used the ashes he found in the crematoria of Majdanek to make a painting. This “art” is displayed in an “art” gallery in Lund, Sweden, and I was left with some questions.

What happened here? Why are the Polish police investigating this artist? We know the Polish do not like to hear the words “Polish death camp” — only “German death camp.” We know they had no problem living in Lublin together with Majdanek. They surely heard the loud music playing on November 3, 1943, and they heard the machine guns and the screams.

They were not troubled then. Why are they troubled now by Hausswolf? Are they suddenly feeling concern for the victims of Majdanek, that their ashes should be undisturbed? Are they protecting their state museum, that nothing should be taken from it?

I wonder what they are thinking, now, 70 years later. And I really wonder: When will the Jews who were murdered in Majdanek get justice?

Ruth Lichtenstein

Publisher

Survivor Reb Moshe Bornstein, shlita, was sent to Majdanek after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. “I felt I will not make it” in Majdanek, he says.

This article appeared in print on page D22 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.