Iconic Felder’s Shul Destroyed in Fire

A fire broke out in the building housing Bais Aharon shul on 18th Ave. at 49th street in Boro Park last Wednesday, destroying the interior of the landmark shul known to generations of Jews as “Felder’s.”

The building’s residents were all rescued, and there were no injuries. The sifrei Torah were in a fireproof safe, though one suffered water damage, and it is not yet known whether it can be saved.

The FDNY has told Hamodia that the cause of the fire remains under investigation.

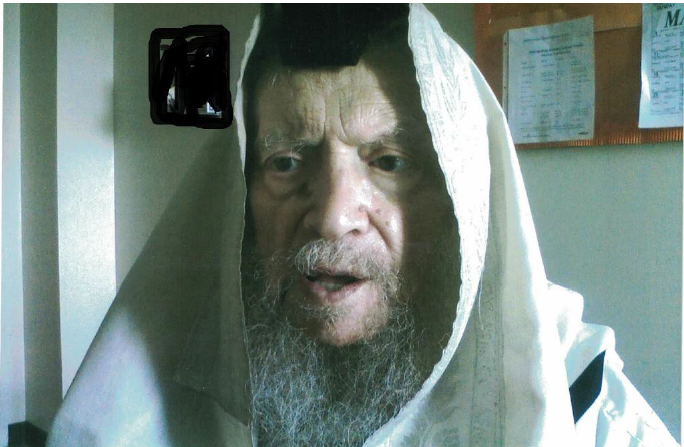

A decision has not yet been made as to whether the shul will be rebuilt. For the tens of thousands who passed through the shul’s doors over its seven decades — to catch a minyan, listen to a shiur, or speak with its legendary rav, Rabbi Hershel (Tzvi Mordechai) Felder — the fire might mean the end of an institution that was for years the epicenter of Yiddishkeit in what was, once upon a time, the “outskirts” of Boro Park.

**

Rabbi Hershel Felder, zt”l, emigrated to America in 1920, from a small town called Wola Michowa, Galicia, at the age of six. His father, Reb Aharon Felder, was a talmid chacham who had learned in the yeshivah of the Arugas Habosem, and worked as a watchmaker.

When the Bobover Rav arrived in New York after World War II and established a trade school for his Chassidim, Reb Aharon Felder taught watchmaking at the school on the West Side of Manhattan.

Reb Aharon wanted his son Hershel, a young talmid chacham, to learn a trade as well, desiring that he not earn his living from “kehalishe gelt.” But it quickly became apparent that Reb Hershel was more cut out to be a rav than a businessman.

Reb Hershel and his wife Chaya lived in Mountaindale, N.Y., where he served as Rebbi in a Talmud Torah, before moving to Boro Park in the late 1940’s, where Reb Hershel held minyanim in his apartment on 52nd Street between 16th and 17th Avenues.

In 1952, Reb Aharon placed a down payment on a building at the corner of 18th Ave. and 49th Street that would serve as a home and shul for his son and daughter-in-law. Rabbi Felder named the shul Bais Aharon, in honor of his father.

For young and even middle-aged Boro Park residents who know the shul as the “minyan factory” it would eventually became, it is difficult to believe how the neighborhood looked back in the shul’s early years.

“At that time, the Jewish neighborhood of Boro Park ended at 16th Avenue; maybe a few families were moving closer to 17th,” says State Sen. Simcha Felder, a son of Rabbi Hershel Felder, and one of several people who shared memories of the shul with Hamodia during the past week. “18th Avenue was michutz lamacheneh. The area was Italian and Irish. Maybe 10% of the families were Jewish, and most non-religious. My parents were one of only two frum families that lived on 49th Street. Today, there are only two non-frum families living on that block.”

Many Jewish families in the area, including Orthodox ones, sent their children to public school in the 1950’s, and Rabbi Felder opened a talmud Torah in his shul, where these children received their Jewish education, free of charge, at 3:00 p.m. every day.

The shul building was a two-story home, plus a basement. The Felders rented out two apartments on the upper floor, and lived on the first floor. The shul was in what would have been the living room/dining room area. The family’s living quarters at first consisted of just the back of the house: a kitchen, dinette, and two bedrooms for the parents and five children. The basement was a cellar used for storage, and where the children played. “Some of the best times of my childhood were spent in the basement,” says the 62-year-old senator. “That’s where we had pillow fights, played hide and seek — that basement was a great place!”

As the children grew older, and separate bedrooms were needed for the two girls and three boys, the family extended the house into the garage behind it, gaining an additional bedroom and a living/dining area. Beginning with the Shabbos of Simcha’s bar mitzvah in 1971, the basement was converted into a shul as well.

But at first, just scraping together a minyan was difficult. Sen. Felder recalls his father once asking a chassan during sheva brachos if it would be alright if he called him to come to Shacharis in case they needed him to complete a minyan.

Even the minyan factory that the shul would become in later years was born with great difficulty.

During the early years, anytime someone had a chiyuv for the amud and needed a minyan, Rabbi Felder would go to exhaustive lengths to ensure he had one.

“I don’t ever remember my father asking anyone for anything,” says Sen. Felder, “except two things: One, when it came to shidduchim for the children, he used to ask total strangers, anyone or everyone he could speak to, whether they have a shidduch for his kids. And the other thing is with the minyan — he stood outside in the cold and the heat, asking people to come inside if someone had a chiyuv and needed a minyan.”

Many of these people who were chiyuvim were not regular mispallelim; Rabbi Felder happily did favors for anyone, even those from other neighborhoods.

“I remember a total stranger from a different part of Boro Park came to my father and said he was a chiyuv, and he heard from somebody that Rabbi Felder can help him with a minyan,” recalls the senator. “My father asked the man when he would like to daven, and the man said, ‘6:30 a.m.’ So my father made calls, stood outside, asked people to come in, and he got a 6:30 minyan for that man.”

At times, Rabbi Felder would even take a car service to pick up mispallelim.

The rav’s determination to ensure that anyone who needed a minyan would have one led to the shul eventually becoming a minyan factory, as the neighborhood grew and 18th Ave. became a central thoroughfare of Jewish Boro Park. By the mid-1980’s, the shul had six daily Shacharis minyanim, and constant minyanim for Minchah and Maariv.

And throughout the day, the shul held various shiurim as well.

“My father was more than happy to have others give shiurim in his own shul,” recalls the senator. “He gave a shiur between Minchah and Maariv, and said divrei Torah at shalosh seudos; otherwise, the shiurim were given by other people — anyone who wanted to give one, which led to a great variety of shiurim and maggidei shiur.”

Daf Yomi in Yiddish and English, Tanya, Orach Chaim — whatever shiur you wanted, you could find at the tiny Felder’s Shul. The sanctuary was subdivided by a folding door, and shiurim would be held while minyanim were taking place on the other side of the door. Every nook and cranny of the building was used for avodas Hashem.

One of the maggidei shiur was Rav Chaim Feifer, z”l, a former talmid of Baranovitch and Kletzk, who worked as head of the alumni association of Ponovez Yeshiva.

“My family moved in 1972 from Crown Heights to 1819 50th Street in Boro Park, and Felder’s became our family shul,” recalls Rabbi Menachem Feifer, a son of Rav Chaim, who serves as rav at the Agudah of Bayswater. “My father had a key to the shul, because he was one of the first to arrive every day, at 5:00 a.m. He learned until it was time to give his Daf Yomi shiur in the back room of the basement, which preceded the 7:40 minyan.

“While my father would learn, there were other minyanim going on. I once asked him why he chose to learn in a shul with so many minyanim. Just across the street, there was a bigger shul that was empty until Shacharis started. My father said, ‘Don’t you understand? That’s exactly why I am learning here. From 1941 to 1946, while I was in Siberia, I couldn’t answer a single Kaddish, Kedushah or Barchu. Now I am able to make that up; while I am learning, I can answer, Kaddish, Kedushah and Barchu.’”

Rav Chaim Feifer was the unofficial “rav” of the 7:40 Shachris minyan— the shliach tzibbur would wait for him to complete Shema and Shemoneh Esrei. Rav Dovid Kviat had the same role at the 8:00 Shacharis minyan.

These were just two of many talmidei chachamim who regularly davened and learned at Felder’s.

“There was Harav Yitzchok Reitport, shlita, who used to also give shiurim and printed kuntressin and gave them out,” recalls Rabbi Feifer, who himself would speak between Minchah and Maariv on Yamim Tovim. “Rav Yankel Neuberger, z”l, gave Daf Yomi also. Rav Leibel Wulliger, Rosh Kollel in Torah Vodaath, davened there. Chazzan Lazer Weinreb used to daven at the amud. My brother-in-law, Rabbi Heshy Wolf of Yeshiva Torah Vodaas, gave a dvar Torah after the 8:30 Shacharis on Shabbos.”

When the Ponovezer Rav, zt”l, was in Brooklyn, he would daven at Felder’s as well, recalls Rabbi Moshe Chaim Felder of Bais Medrash Elyon, a brother of the senator. “At Shacharis, people used to wait for the Ponovezer Rav to finish Shemoneh Esrei — but he would bang on the table and insist that they go ahead.

“When Harav Yaakov Horenstein, z”l, davened there, my father would try to walk him to the door, but he never wanted to be matriach my father. My father would say, ‘I just want to get some fresh air,’ and Rav Horenstein would say, ‘There’s better air the other way.’”

Everyone felt at home at Felder’s — the biggest talmidei chachamim, baalei battim who were kovei’a ittim laTorah, and those who simply came to get strength and support from Rabbi Felder.

“It was a place where people who needed chizuk would come — many people would not feel comfortable in other shuls, but Rabbi Felder welcomed everyone,” says Rabbi Feifer. “The downtrodden, lost souls, all would come, to daven, to listen to shiurim, or just to get chizuk — he went out of his way to make everyone comfortable.”

On Shabbos morning, the downstairs minyan was specially for bachurim — run by a future state senator.

“Simcha ran the shul in many ways, made it geshmak, adding a tremendous life to the minyan downstairs,” says Rabbi Feifer. “It was such an enjoyable place to be — lively and friendly and warm. He had such a good sense of humor, and made everyone who davened there feel it was their shul.”

The shul hardly brought in any money; for decades, into the 21st century, seats for Yamim Nora’im were $18; eventually they rose to $36, and then the current price of $54. Mrs. Felder was a full-time housewife, mother and rebbetzin. The family’s income came from the rent from the two tenants upstairs, and from Rabbi Felder’s work as an eid or a member of a beis din. But Rabbi and, tbl”c, Rebbetzin Felder seemingly had no material desires, living only for others.

“Rabbi Felder was an absolutely unique and selfless person,” recalls Rabbi Shmuel Boruch Tress, who was chazzan at Felder’s on Yamim Nora’im for more than three decades. “During all the years I was at the shul, I don’t know if he ever sat in his seat; there were always other people sitting there. His whole Olam Hazeh was to create minyanim and shiurim.

“He and the rebbetzin barely owned a complete piece of furniture. They had maybe a table here, a chair there, no sets, nothing matching. They raised a family in America in the way that Torah families used to be raised in Europe or today in Eretz Yisrael — and you can see the results, how their children are talmidei chachamim and oskim b’tzorchei tzibbur b’emunah.

“Rabbi Felder was so humble; he had absolutely no ego, he was almost non-existent. Even in later years, when there were many shuls in the area, people still flocked to his little shul; the attraction to Rabbi Felder’s shul, and what made it so popular, was Rabbi Felder.

“And whatever he did, he never could have accomplished without his dedicated rebbetzin. She gets so much credit for happily living the lifestyle that he did — forgoing material comforts and supporting all her husband’s activities. She was not only beloved by all the women in the neighborhood, but she was a shining example of a true eishes chayil, and enthusiastically supported all her husband’s activities, helping the shul flourish. To her, this lifestyle was not a sacrifice, but a zechus.”

And the Felders’ chassadim extended far beyond the shul doors.

Someone once asked Rabbi Felder if he could visit an elderly, invalid widower. Not only did Rabbi Felder go visit him, but he developed a relationship and bathed him every week as well.

Rabbi Tress recalls: “Rabbi Felder would wake up early, so he went to sleep very early, too. But one night he called me at 10 p.m. and asked if I could do him a favor. I said, ‘You know I would do anything, anytime for you — the only question I have is what are you doing up at 10 o’clock?’ He replied, ‘As I was going to sleep, I remembered that I made a promise to someone and I can’t go to sleep until I fulfill that promise.’”

Near the shul there was an Israeli car service; a driver who barely spoke English had walked into the shul that day between Minchah and Maariv, and told Rabbi Felder that a friend of his, who had no family, had been taken to Coney Island Hospital.

“I have no idea why this driver came to Rabbi Felder — he must have heard of all the chassadim he did — but Rabbi Felder wrote down the name of the patient and said he would go see him before the day was over. Now, as he was getting ready for bed, he remembered that he had not visited him — and couldn’t go to bed without keeping his promise.”

Rabbi Tress drove Rabbi Felder to the hospital. The patient was grateful for the visitors. Rabbi Felder then asked if he was getting kosher food, but the man did not seem to care. “Rabbi Felder spent time explaining how important kashrus is, and the man agreed to eat the kosher food,” says Rabbi Tress. “As we left, Rabbi Felder stopped at the nurses’ station to request that this person get kosher food.”

**

Even as the neighborhood changed, Rabbi Felder’s mission never did.

The Talmud Torah Bais Aharon ended in the early 1960’s — by then, yeshivos were flourishing in Boro Park. But the sign in front of the shul, “Give your child a Jewish education — enroll them in Talmud Torah Bais Aharon” under “Rabbi Harry Felder,” remained up for years.

Simcha Felder recalls, “When I was in yeshivah, the kids used to make fun of me for that sign. I used to beg my father that he should tear down the sign. I’d say, ‘It’s not true — there’s no Talmud Torah anymore.’ But my father insisted on keeping it up . He’d say, ‘It is true, because if anybody comes in and wants their kid to have a Jewish education, I will teach them for free.’”

One hot summer day, when Simcha was 11 years old, a woman, obviously non-religious and immodestly dressed, walked up to the shul steps and told Simcha, standing outside, that she wanted to give her child a Jewish education. Simcha was terribly embarrassed.

“I said, ‘There is no Talmud Torah anymore.’ But she said, ‘There is a sign, and the Rabbi would not lie.’ I said, ‘The Rabbi is giving a class.’ She said, ‘I’ll wait.'” She waited, and when she got to speak to Rabbi Felder, told him that she wanted him to teach her son. Rabbi Felder agreed, on one condition: that her husband, though he worked on Shabbos, would bring their son to shul on Shabbos.

Five decades later, the man who was this young child has grandchildren learning in Chassidishe yeshivos. All because Rabbi Felder refused to take down the sign, because his offer to teach any Jewish child for free was always open.

“And as many incidents as you may hear about,” says Rabbi Tress, “there are countless stories and episodes that will never be known. These stories” that are publicized, says Rabbi Tress, “are just a tiny fraction among the endless chassadim, activities and dedication” of Rabbi and Rebbetzin Felder, and their little shul on a busy corner of Boro Park.

“I’m telling you, if you didn’t experience this, it’s impossible to understand.”

Rabbi Felder was niftar on Taanis Esther 12 years ago, but the shul continued on, with the dedication of his rebbetzin and children.

As the years went by and many more shuls opened in the neighborhood, the minyan factory was not needed as before. The frequency of the minyanim at Felder’s waned somewhat, but until the day of the fire last Wednesday, the shul still had a daily Shacharis minyan, and many Minchah and Maariv minyanim.

Considering that there is less of a need for the shul now, the Felder family is unsure whether they will rebuild the shul, and are consulting daas Torah on the matter.

“After the fire,” says the senator, “a long-time mispallel said to me that when my father passed away, he did not feel like he was niftar – since the shul was so much his life, it felt like he really hadn’t passed away. But when he saw the fire, he said that he felt like Rabbi Felder was niftar on that day.”

“In large part,” says Simcha Felder, who grew up in a relatively irreligious section of Boro Park, played in the basement of the shul as a child, witnessed the neighborhood grow and flourish, watched many shuls spring up around him, but saw so many still drawn to the small yet world-famous building on 18th and 49th, an area he would go on to represent in the New York City Council and then the State Senate, “this side of Boro Park developed as a result of my parents’ mesirus nefesh in the early years.”

“For the many of us who were fortunate to spend our formative years in the 18th Avenue area of Boro Park,” says Rabbi Feifer, “the iconic Felder’s shul was an essential part of our lives — and always will be.”

A man once asked Rabbi Felder about the other shuls in his area. The elderly rav had moved to the neighborhood years earlier, and built the shul with blood, sweat and tears, standing in the heat and cold and scrounging for minyanim. “Now that you finally built up your shul,” the fellow asked, “does it bother you that competitors are opening all over the place?”

“They’re not my competitors,” Rabbi Felder replied. “They’re my branches.”

—

rborchardt@hamodia.com

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.