In The Developing World, the Coronavirus Is Killing Young People, Too

When the coronavirus first came to Brazil and a call went out for volunteers to work the critical care wards, Isabella Rêllo analyzed the risks. She was 28. She lived alone. She didn’t have pre-existing conditions.

So while older physicians stepped back from the front lines of the coronavirus response, Rêllo stepped up.

Soon Rêllo, a pediatrician, was treating dozens of coronavirus patients. But they weren’t who she’d expected. This patient was only 30 years old. That one was 32. Nearly half the people she was seeing were young, she said, and many were dying. The narrative seared into the global consciousness in the early months of the pandemic – that the virus spared the young and ravaged the elderly – was not what she was watching unfold in Brazil.

The young were at risk. She was at risk.

“One patient was young, apparently healthy,” she said. “He was so sick, with so many complications. I thought, ‘This could be me. He could be my friend.’ The quickness that this kills people, including the young, has been a shock.”

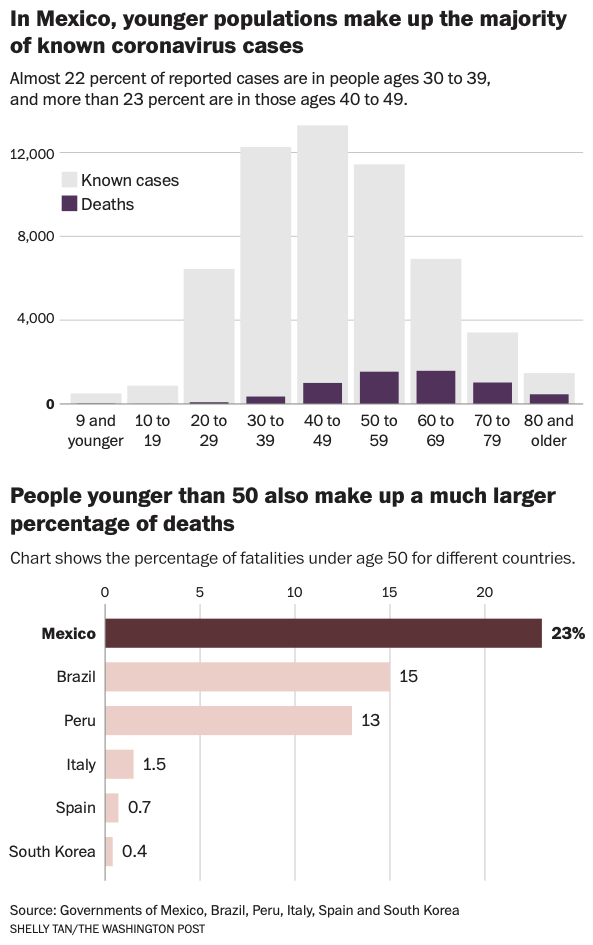

As the coronavirus escalates its assault on the developing world, the victim profile is beginning to change. The young are dying of covid-19 at rates unseen in wealthier countries – a development that further illustrates the unpredictable nature of the disease as it pushes into new cultural and geographic landscapes.

In Brazil, 15 percent of deaths have been people under 50 – a rate more than 10 times greater than in Italy or Spain. In Mexico, the trend is even more stark: Nearly one-fourth of the dead have been between 25 and 49. In India, officials reported this month that nearly half of the dead were younger than 60. In Rio de Janeiro state, more than two-thirds of hospitalizations are for people younger than 49.

“This is new terrain compared to what’s happened in other countries,” said Daniel Soranz, the former municipal health minister in Rio de Janeiro. “Brazil is a very important country to be looking at.”

Analysts say the emerging data suggests many of the problems that have long troubled the developing world – intractable poverty, extreme inequality, fragile health systems – are increasing vulnerability to the disease. In countries with more poverty and fewer resources, people who might have survived elsewhere are instead dying.

George Gray Molina, chief economist for the United Nations Development Program, said poverty is triggering “compounding effects.” Because population density is so much higher in much of the developing world – and because so many people must keep working to survive – a far greater share of the population ends up being exposed to the virus.

The virus then spreads through a population that’s less resilient. People in the developing world grapple not only with the diseases that have long been associated with it – malaria, dengue, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases – but increasingly with those more closely associated with wealthier countries. Rates of diabetes, obesity and hypertension are surging. But treatment for many such illnesses is lacking.

When newly infected coronavirus patients already weakened by pre-existing conditions seek treatment, they find hospital systems that are overwhelmed and unequipped to handle the deluge of patients.

“It all points to social economic status and poverty,” Gray Molina said. The positive benefits associated with the developing world – such as younger populations – are being “wiped out.”

“As this plays out,” he said, “we will see a balancing of the scales.”

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.