Four Dead as Train Derails on Fast Curve in Bronx

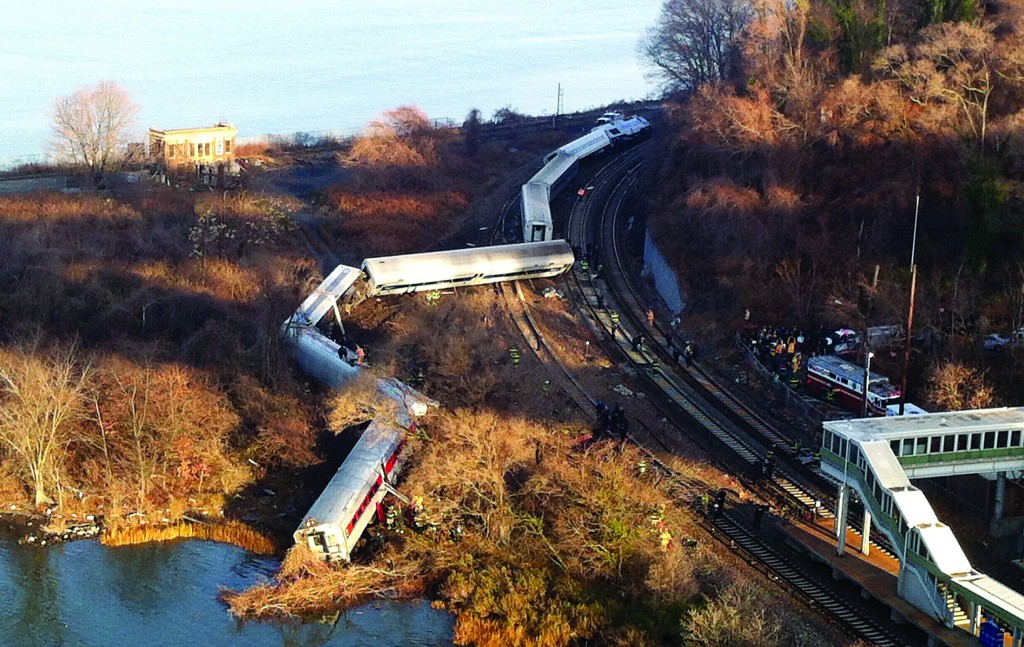

A commuter train rounding a riverside curve derailed Sunday, killing four people and injuring more than 60 in a crash that threw passengers from the toppling cars and left a snaking chain of twisted wreckage just inches from the water.

Some of the roughly 150 passengers on the early-morning Metro-North train from Poughkeepsie to Manhattan were jolted from sleep around 7:20 a.m. by screams and the frightening sensation of their compartment rolling over on a bend in the Bronx where the Hudson and Harlem rivers meet. When the motion stopped, four or five of the seven cars had lurched off the rails. It was the latest accident in a troubled year for the nation’s second-biggest commuter railroad, which had never experienced a passenger death in an accident in its 31-year-history.

“Four people lost their lives today,” Gov. Andrew Cuomo said somberly at a news conference. Eleven of the injured were believed to be critically hurt and another six seriously hurt. The train operator was among the injured.

The governor said the track did not appear to be faulty, leaving speed as a possible culprit for the crash. But he noted that the National Transportation Safety Board would determine what happened. The Federal Railroad Administration was also sending 10 investigators to the scene.

The governor said the track did not appear to be faulty, leaving speed as a possible culprit for the crash. But he noted that the National Transportation Safety Board would determine what happened. The Federal Railroad Administration was also sending 10 investigators to the scene.

MTA chairman Thomas Prendergast said investigators would look at numerous factors, including the train, the track and signal system, the operators and speed. The speed limit on the curve is 30 mph, compared with 70 mph in the area approaching it. The train’s data recorders should be able to tell how fast it was traveling.

One passenger, Frank Tatulli, told WABC that the train appeared to be going “a lot faster” than usual as it approached the sharp curve near the Spuyten Duyvil station, which takes its name from a Dutch word for a local waterway.

The train was about half full at the time of the crash, rail officials said, with some passengers likely heading to the city to shop.

Joel Zaritsky was dozing as he traveled to a dental convention.

“I woke up when the car started rolling several times. Then I saw the gravel coming at me, and I heard people screaming,” he said, holding his bloody right hand. “There was smoke everywhere and debris. People were thrown to the other side of the train.”

Nearby residents awoke to a building-shaking boom. Angel Gonzalez was in bed in his high-rise apartment overlooking the rail curve when he heard the roar.

“I thought it was a plane that crashed,” he said.

“I thought it was a plane that crashed,” he said.

Within minutes, dozens of emergency crews arrived and carried passengers away on stretchers, some wearing neck braces. Others, bloodied and scratched, held ice packs to their heads.

Firefighters shattered the windows of the toppled train cars to reach passengers, and they used pneumatic jacks and air bags to make sure they uncovered any victims who might have been pinned by train seats or other objects.

Police divers searched the waters to make sure no one had been thrown in. Other emergency crews scoured the surrounding woods.

Three men and one woman were killed. Three of the dead were found outside the train, and one was found inside. The victims’ names have not yet been released.

Victims with a spinal cord injury, an open leg fracture and other broken bones were being treated at St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, one of the medical facilities that took patients.

“It looked like a toy train set that was mangled by some super-powerful force,” Gov. Cuomo said in a phone interview with CNN.

As deadly as the derailment was, the toll could have been much worse had it happened on a weekday or had the lead car plunged into the water instead of coming to rest on its edge.

“On a workday, fully occupied, it would have been a tremendous disaster,” the city’s fire commissioner, Salvatore Cassano, told reporters at the scene.

Amtrak Empire service was halted for hours between New York City and Albany but resumed Sunday afternoon, with some delays. It was not clear when service would resume on the affected part of Metro-North’s Hudson line, which carries about 18,000 people on an average weekday morning.

Amtrak Empire service was halted for hours between New York City and Albany but resumed Sunday afternoon, with some delays. It was not clear when service would resume on the affected part of Metro-North’s Hudson line, which carries about 18,000 people on an average weekday morning.

Westchester County Executive Rob Astorino said contingency plans were in the works for Monday-morning rush hour, possibly using buses.

Sunday’s accident was the second passenger train derailment in six months for Metro-North. On May 17, an eastbound train derailed in Bridgeport, Conn., and was struck by a westbound train. The crash injured 73 passengers, two engineers and a conductor. Eleven days later, track foreman Robert Luden was struck and killed by a train in West Haven, Conn.

In July, a freight train full of garbage derailed on the same Metro-North line near the site of Sunday’s wreckage.

“Safety is clearly a problem on this stretch of track,” state Sen. Jeff Klein, who represents the nearby area, said Sunday.

Earlier this month, Metro-North’s chief engineer told members of the NTSB investigating the May derailment that the railroad is “behind in several areas,” including a five-year schedule of cyclical maintenance that had not been conducted since 2005.

The NTSB issued an urgent recommendation to Metro-North that it use “redundant protection,” such as a procedure known as “shunting” in which crews attach a device to the rail in a work zone alerting the dispatcher to inform approaching trains to stop.

This article appeared in print on page 1 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.