Bloomberg Furiously Denounces Stop/Frisk Ruling

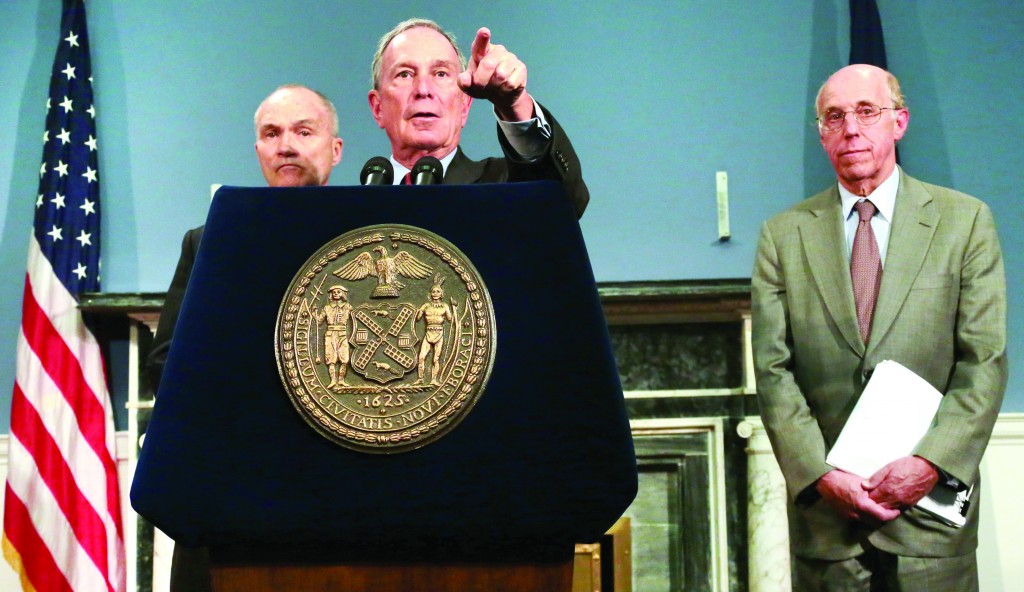

The ruling Monday that the New York police department illegally singled out blacks and Hispanics under its controversial stop-question-and-frisk policy is a dangerous and unprecedented one, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, flanked by NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly and Michael Cordoza, the city’s legal counsel, said in a press conference.

“Throughout the trial that just concluded, the judge made it clear she was not at all interested in the crime reductions here or how we achieved them,” Bloomberg said about U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin, who issued her long-awaited ruling hours earlier, about three months after the 10-week trial.

“In fact, nowhere in her 195-page decision does she mention the historic cuts in crime or the number of lives that have been saved.”

Scheindlin, who had at times during the trial almost seemed as if she was advising the plaintiffs on how to present their arguments, was slammed by the mayor and Kelly in unusually harsh terms — especially her appointing an independent monitor to oversee major changes, including body cameras on some officers.

“No federal judge has ever imposed a monitor over a city’s police department following a civil trial,” Bloomberg said. “The Department of Justice — under Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama — never, not once, found reason to investigate the NYPD.”

“But one small group of advocates — and one judge — conducted their own investigation,” Bloomberg said, a note of sarcasm in his voice. “And it was pretty clear from the start which way it would turn out.”

“What I find most disturbing and offensive about this decision,” Kelly said, “is the notion that the NYPD engages in racial profiling. That simply is recklessly untrue. We do not engage in racial profiling; it is prohibited by law, it is prohibited by our own regulations. We train our officers that they need reasonable suspicion to make a stop, and I can assure you that race is never a reason to conduct a stop.”

Bloomberg said he would appeal the ruling, which would overturn a policy he has defended as a lifesaving, crime-fighting tool that helped lead the city to historic crime lows.

“She ignored the real-world realities of crime, the fact that stops match up with crime statistics, and the fact that our police officers on patrol — the majority of whom are black, Hispanic, or members of other ethnic or racial minorities — make an average about less than one stop a week,” he said.

But Scheindlin issued a stinging rebuke to the mayor in her ruling, calling the tactic that statistics show saved more than 7,000 lives of minority individuals over the past 10 years discriminatory.

“The city’s highest officials have turned a blind eye to the evidence that officers are conducting stops in a racially discriminatory manner,” Scheindlin wrote. “In their zeal to defend a policy that they believe to be effective, they have willfully ignored overwhelming proof that the policy of targeting ‘the right people’ is racially discriminatory.”

Stop-and-frisk has been around for decades in some form, but recorded stops increased dramatically under the Bloomberg administration to an all-time high in 2011 of 684,330, mostly of black and Hispanic men. The lawsuit was filed in 2004 by four men, all minorities, and became a class-action case.

About half the people who are stopped are subject only to questioning. Others have their bag or backpack searched, and sometimes police conduct a full pat-down. Only 10 percent of all stops result in arrest, and a weapon is recovered a small fraction of the time.

Scheindlin noted she was not putting an end to the practice, which is constitutional, but was reforming the way the NYPD implemented its stops.

In her long ruling, she determined at least 200,000 stops were made without reasonable suspicion, the necessary legal benchmark, lower than the standard of probable cause needed to justify an arrest. She said that rank-and-file officers were pressured by superiors to make stops — and that high-ranking police officials ignored mounting evidence that bad stops were being made.

“The city and its highest officials believe that blacks and Hispanics should be stopped at the same rate as their proportion of the local criminal suspect population,” she wrote. “But this reasoning is flawed because the stopped population is overwhelmingly innocent — not criminal.”

In his press conference, Bloomberg said that the reason minorities are disproportionately stopped is a societal problem — the majority of high-crime areas are in their neighborhoods. He said that the city has also been directing more social services to those vicinities to solve the problem in the long term.

“[Police] fight crime wherever crime is occurring,” he said, “and they don’t worry if their work doesn’t match up to a census chart.”

Scheindlin did not give many specifics for how to correct the practices, but instead directed the monitor to develop reforms to policies, training, supervision and discipline with input from the communities most affected. She also ordered a pilot program in which officers test body-worn cameras in the one precinct per borough where most stops occurred. The idea came up inadvertently during testimony, but Scheindlin seized on it as a way to provide objective records of the encounters.

Scheindlin appointed Peter L. Zimroth, the city’s former lead attorney and previously a chief assistant district attorney, as the monitor.

Bloomberg said police have done exactly what the courts and constitution allow to keep the city safe. The judge simply does not understand “how policing works,” he said, and the result could be a return to the days of crime and mayhem from the 1980s and 1990 — when murders hit an all-time high of 2,245.

“This is a dangerous decision,” he said. “… I worry for my kids, and I worry for your kids. I worry for you and I worry for me. Crime can come back any time the criminals think they can get away with things. We just cannot let that happen.”

City lawmakers have also sought to create an independent monitor and make it easier for people to sue the department if they feel their civil rights were violated. Those bills are awaiting an override vote after the mayor vetoed the legislation.

The monitor appointed Monday will examine stop-and-frisk specifically and can compel changes. The inspector general envisioned in the city legislation would look at other issues but could only make recommendations.

The appeal process could take time, and the ruling will likely be on hold, meaning one of the candidates running in the November election to succeed Bloomberg will deal with the outcome.

Overall, the Democrats running to replace Bloomberg issued statements hailing the ruling, while the Republicans promised to continue stop-question-and-frisk as allowed under the law.

“In the strongest possible terms, I urge Mayor Bloomberg not to appeal the judge’s ruling,” City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, a Democrat, said. “We need to move forward with the monitor, move forward with the inspector general.”

Joe Lhota, a Republican, urged Bloomberg to appeal for a delay in the ruling.

“The NYPD is one of the most closely scrutinized law enforcement agencies in the country,” he said. “… The last thing we need is another layer of outside bureaucracy dictating our policing.”

Republican John Catsimatidis said he was disappointed by the ruling.

“The [NYPD] is the best in the world; their innovative crime- fighting tactics are a model for law enforcement worldwide,” he said. “Today’s decision should not be viewed as an indictment of their tactics.”

With reporting by The Associated Press

This article appeared in print on page 1 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.