Bloomberg Vows to Fight Laws Reining In NYPD

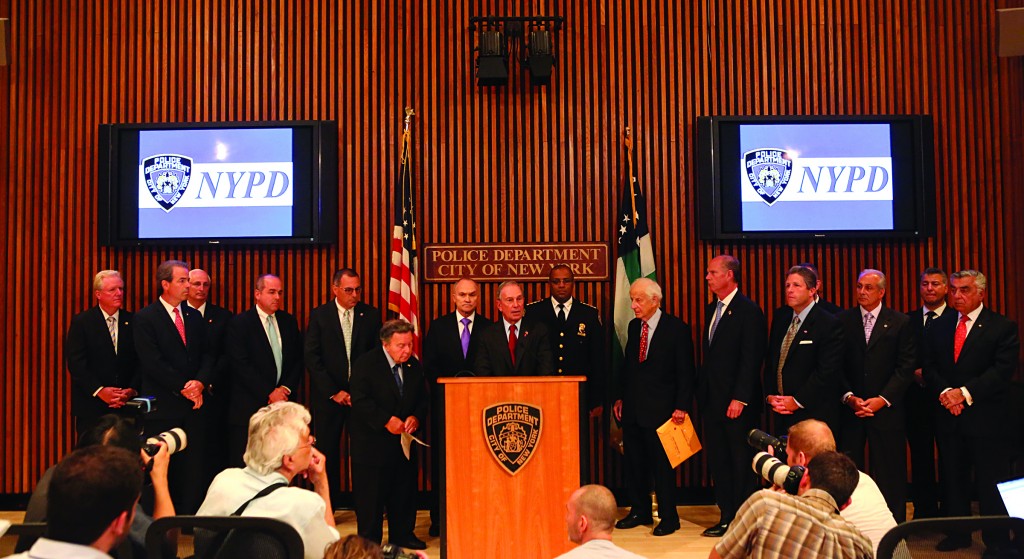

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said Thursday they won’t stop fighting lawmakers’ plans to increase oversight of police, hours after the City Council passed by a veto-proof majority the most expansive plans in years to create an outside watchdog and make it easier to bring racial profiling claims against the nation’s largest police force.

“Last year, there were a record-low number of murders, and a record-low number of shootings, in our city, and this year we’re on pace to break both of those records,” Bloomberg said in a statement. “Unfortunately, these dangerous pieces of legislation will only hurt our police officers’ ability to protect New Yorkers and sustain this tremendous record of accomplishment.”

Bloomberg said at a news conference Thursday he “will not give up for one minute” on trying to defeat the measures. He tells New Yorkers it’s “a fight to defend your life and your kids’ lives.”

Kelly slammed the council’s move as misguided, one with the potential to increase crime and make officers’ jobs more difficult.

“This is going to affect everyone in the city; it’s not just going to affect the police department,” Kelly said at a news conference Thursday morning. “Shootings are at record lows. Some people apparently are not satisfied with that. We’re going to see what this all means if the mayor’s veto is not sustained.”

Both bills passed with a sufficient majority of legislators who could potentially override a veto, an act Bloomberg promised within the required 30 days. The council would then have an additional 30 days to override it by a two-thirds majority of 34 out of the 51 votes.

The bill establishing an outside inspector passed by a comfortable 40-11 margin, making it likely to survive a veto. The profiling bill, on the other hand, squeaked by with just 34 votes in favor, meaning that Bloomberg has to convince only one legislator to back out and the law would not take effect.

Practically all of New York City’s police unions promised to withdraw their endorsements of any council member who voted in favor of the more intrusive racial-profiling bill.

“Any legislator who supports an irresponsible bill like this is not worthy of the political support of the men and women who risk their lives behind the gold shield,” Michael Palladino, president of the Detectives Endowment Association, which has so far made 30 endorsements, told the New York Post.

“It indicts everyone who wears blue,” said Roy Richter, president of the Captains Endowment Association. “They’re placing the burden of proof on police to prove that they did not act with bias.”

In a rare council session that extended until past 2 a.m., councilmen posted pictures of themselves online with their smartphones as they each took two minutes to explain their votes. A light moment came when the lights momentarily went out in the middle of Councilman Jumaane Williams’ speech, prompting Speaker Christine Quinn to wonder if the council had paid its ConEd bill.

“Remember the 1990s? We’re going back,” Councilman Peter Vallone, a conservative Democrat from Queens, said as he voted against both bills.

As the 34th councilman voted for the bill to make it easier to sue over racial profiling, Williams, who along with Councilman Brad Lander spearheaded the measures, jumped out of his seat, pumping his fists in the air.

“New Yorkers know that we can keep our city safe from crime and terrorism without profiling our neighbors,” Lander said at a packed and emotional meeting that began shortly before midnight.

Lawmakers delved into their own experiences with the street stops, drew on the city’s past in episodes ranging from the high crime of the 1990s to the 1969 Stonewall riots, and traded accusations of paternalism and politicizing.

“The vast majority who I know are planning to vote against [the bills] do not represent the people who deal with gun violence in their communities,” Williams, a Flatbush Democrat, said. “If you don’t live there, if you haven’t lived through it, if you donrepresent these communities — please side with us.”

All black and Hispanic lawmakers voted for both bills; Peter Koo, a Democrat of Asian extraction representing parts of Queens, was the only non-white to vote against.

“I think we cannot stop people from profiling,” Koo said. “I mean, we all do it every day, either in … business or in other entities.”

Several council members, including Quinn, a Democratic mayoral candidate, and David Greenfield, a conservative Democrat representing Boro Park and Flatbush, voted for the inspector general but not for the stop-and-frisk law.

“I believe [an] inspector general will make [the] NYPD stronger through oversight,” Greenfield commented shortly after voting. “I don’t support [the] profiling law because it puts good cops at risk of lawsuits.”

Charles Barron, a Democrat from south Brooklyn with a reputation for strong language, sparred with several of the bill’s opponents.

“When the mayor doesn’t like it and the commissioner doesn’t like it, it has to be good for the City of New York,” Barron said before voting in support of both bills.

Opposition was led mainly by Vallone and Eric Ulrich, a Queens Republican.

“When the courts are in charge, we will become Chicago. We will become Detroit,” Vallone said. “Crime will soar. Murders will rise. Children will die. It’s not fear-mongering if it’s true.”

When Barron took a shot at him, Vallone responded tartly, “I have spent my life keeping New York safe from people like you.”

“It’s an election year,” Ulrich said. “We all want to pander… Give me a break. I will not be intimidated by the professional police critics, by the panderers, by the media. This is an outrage.”

Councilman Donovan Richards, who represents parts of Brooklyn and Queens, spoke dramatically of a personal encounter at age 16 when he was stopped and frisked.

“Many of you may not understand what it feels like to be stopped and frisked, but I do,” Richards said. “Today, I’m not scared. Today, I’m elected. And I have a chance to do something about it.”

Critics say the measures would impinge on techniques that have wrestled crime down dramatically and would leave the NYPD “pointlessly hampered by outside intrusion and recklessly threatened by second-guessing from the courts,” Bloomberg said. He vowed in a statement minutes after the vote to veto the measures and continue urging lawmakers to take his side.

But while it’s too soon to settle how the initiatives may play out in practice if they survive a veto, they have already shaped politics and perception. The legislation has put the three-term mayor and his popular police commissioner in the uncommon position of possibly losing a high-profile fight on public safety.

They have gone to great lengths to make their criticisms heard, most recently in a Monday news conference at which Bloomberg envisioned gang members lodging discriminatory-policing complaints and Kelly invoked “al-Qaida wannabes.”

Yet on Wednesday, many council members rebuffed those concerns and approved the measures by wide margins.

“It just became so polarized,” Eugene O’Donnell, a John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor who follows issues related to the NYPD, said by phone. “[Bloomberg and Kelly] just dug in their heels, for whatever reason, and they ended up with the City Council coalescing around a pretty dramatic set of steps.”

The measures follow on decades of efforts to empower outside input on the NYPD. Efforts to establish an independent civilian complaint board in the 1960s spurred a bitter clash with a police union, which mobilized a referendum on it. Voters defeated it.

More than two decades later, private citizens were appointed to the Civilian Complaint Review Board, which mainly handles misconduct claims against individual officers. A 1990s police corruption scandal spurred a recommendation for an independent board to investigate corruption; a Commission to Combat Police Corruption was established in 1995, but it lacks subpoena power.

Courts have also exercised some oversight, including through a 1985 federal court settlement that set guidelines for the NYPD’s intelligence-gathering. And the City Council has weighed in before, including with a 2004 law that barred racial or religious profiling as “the determinative factor” in police actions, a measure Bloomberg signed.

The new measures are further-reaching than any of those, proponents and critics agree.

One measure would establish an inspector general with subpoena power to explore and recommend, but not force, changes in the NYPD’s policies and practices. Various law enforcement agencies, including the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department, have inspectors general.

The other would give people more latitude if they felt they were stopped because of bias based on race or certain other factors.

Plaintiffs wouldn’t necessarily have to prove that a police officer intended to discriminate. Instead, they could offer evidence that a practice such as stop-and-frisk affects some groups disproportionately, though police could counter that the disparity is justified to accomplish a substantial law enforcement end. The suits couldn’t seek money, just court orders to change police practices.

The proposals were impelled partly by concern about the roughly five million stop-and-frisks the NYPD has conducted in the last decade. More than 80 percent of those stopped have been black or Hispanic, and arrests have resulted less than 15 percent of the time. Proponents also point to the department’s spying on Muslims, which has included infiltrating Muslim student groups and putting informants in mosques.

The NYPD has defended the surveillance and stop-and-frisks as legal, and critics of the new legislation point to another set of statistics: Killings and other serious offenses have fallen 34 percent since 2001, while the number of city residents in jails and prisons has fallen 31 percent.

Bloomberg has said they could tie the department up in lawsuits and complaints, inject courts and an inspector general into tactical decisions, and make “proactive policing by police officers extinct in our city.”

And several council members agreed with him.

“The unintended consequences, potentially, of these bills is when a human, a man or woman, who has [a] badge will pull their punch and not aggressively pursue a potential perpetrator, and then he or she goes out and commits a crime. That’s the fear,” Republican Councilman Vincent Ignizio told his colleagues Thursday.

If the measures ultimately survive, Bloomberg won’t be in City Hall to see much of the outcome. The term-limited mayor leaves office on Dec. 31 of this year, a day before the bills go into effect.

Democratic mayoral candidates have generally said the practice needs changing. Most of the Republican candidates, meanwhile, have embraced the NYPD’s view.

(With additional reporting by The Associated Press)

This article appeared in print on page 1 of edition of Hamodia.

To Read The Full Story

Are you already a subscriber?

Click "Sign In" to log in!

Become a Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Become a Print + Web Subscriber

Click “Subscribe” below to begin the process of becoming a new subscriber.

Renew Print + Web Subscription

Click “Renew Subscription” below to begin the process of renewing your subscription.